The Space of Making

2005.01.14 - 02.27

- Notes

From January 14 to February 27, 2005, Neuer Berliner Kuntsverein, Berlin

From April 17 to June 19, 2005, Städtische Museum Zwickau, Zwickau

From July 24 to September 18, 2005, Kunstmuseum Heidenheim, Heidenheim

From November 24, 2005 to January 22, 2006, Städtische Galerie Waldkraiburg, Waldkraiburg

In 1969, Jeff Wall published Landscape Manual, a book whose annotated text provided a commentary on the making of landscape photographs; the images illustrating the manual showed a suburban road, with its vacant lots, cars, and houses. By adopting the methodology of a didactic book, Wall provided a critical narrative of the genesis of an urban phenomenon, all the while parodying the “objective” gaze of documentary photography. “The facts always exist in interdependence with your thinking,” Wall wrote in 1970 on the subject of his manual, reiterating the importance of his conceptual project.1

Also in 1969, the N.E. Thing Co., run by a pair of Vancouver artists, Ingrid and Iain Baxter, erected advertising billboards along an ordinary stretch of road in Prince Edward Island. The sequence of photographs that re-create this journey inform us that we are travelling through a Quarter Mile N.E. Thing Co. Landscape. Although the images are still photographs, they ingeniously imitate cinematic ellipsis by linking spaces and times to convey the temporality of the route. After the images, a map that situates the site is displayed, while a drawn sketch retraces the path taken. N.E. Thing Co. is playing with compelling contradictions: the text’s descriptive quality produces a sense of space; the immobility of the images takes us on a journey; and the humour reminds us of photography’s limitations in re-creating spatio-temporal experiences.

Still in 1969, Ian Wallace roamed the boulevards of Vancouver, looking for modern architectural forms superimposed on the urban traces of daily life. His photographs of the period “rigorously” reproduce the classic mistakes of the amateur photographer—imprecise framing, unwanted reflections, indifference to lighting, objects intruding into the field of vision—giving them an ordinary, almost insignificant qua-lity. Nevertheless, this deliberate lack of know-how has the merit of directing our attention to the pictures’ making, which, while not rendering the city and its representation invisible, presents them from the point of view of their materiality.

What these three artists’ conceptual projects have in common is that the process of creating space is not behind the scenes, but constitutes the very substance of their images. Continuing the thought process he had begun twenty-five years earlier with Landscape Manual, Jeff Wall now focuses on what photography had made visible in conceptual practices: “It is possible that the fundamental shock that photography caused was to have provided a depiction which could be experienced more the way the visible world is experienced than had ever been possible previously. A photograph therefore shows its subject by means of showing what experience is like; in that sense it provides ‘an experience of experience’, and it defines this as the significance of depiction.”2 In addition to being invested with ways of thinking about the world, photography reveals ways of making it.

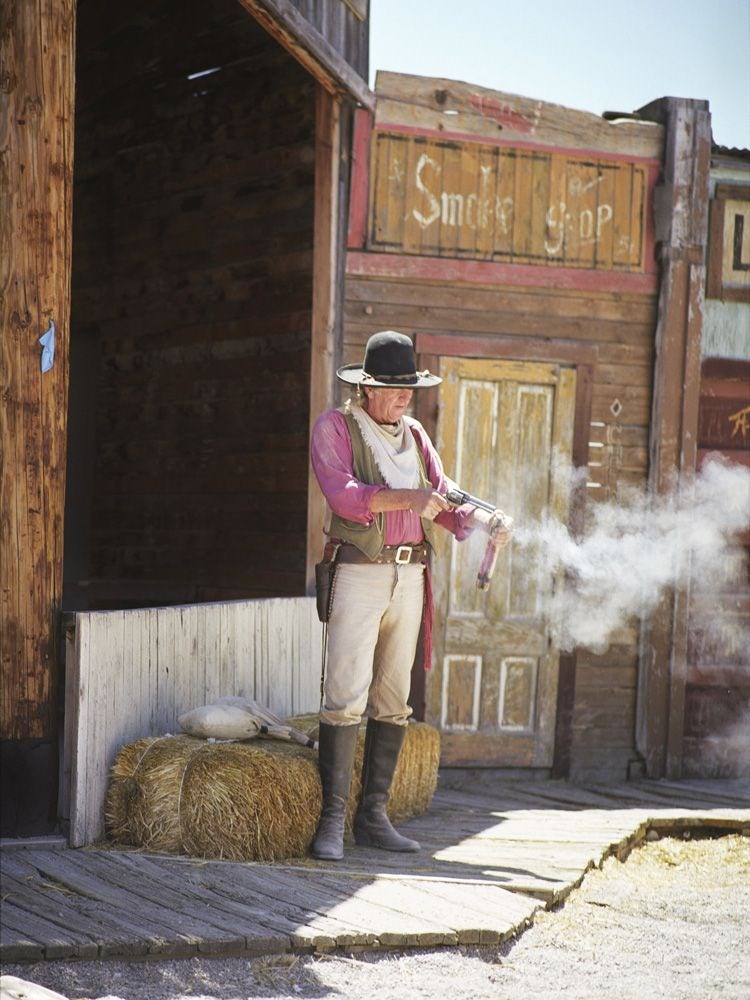

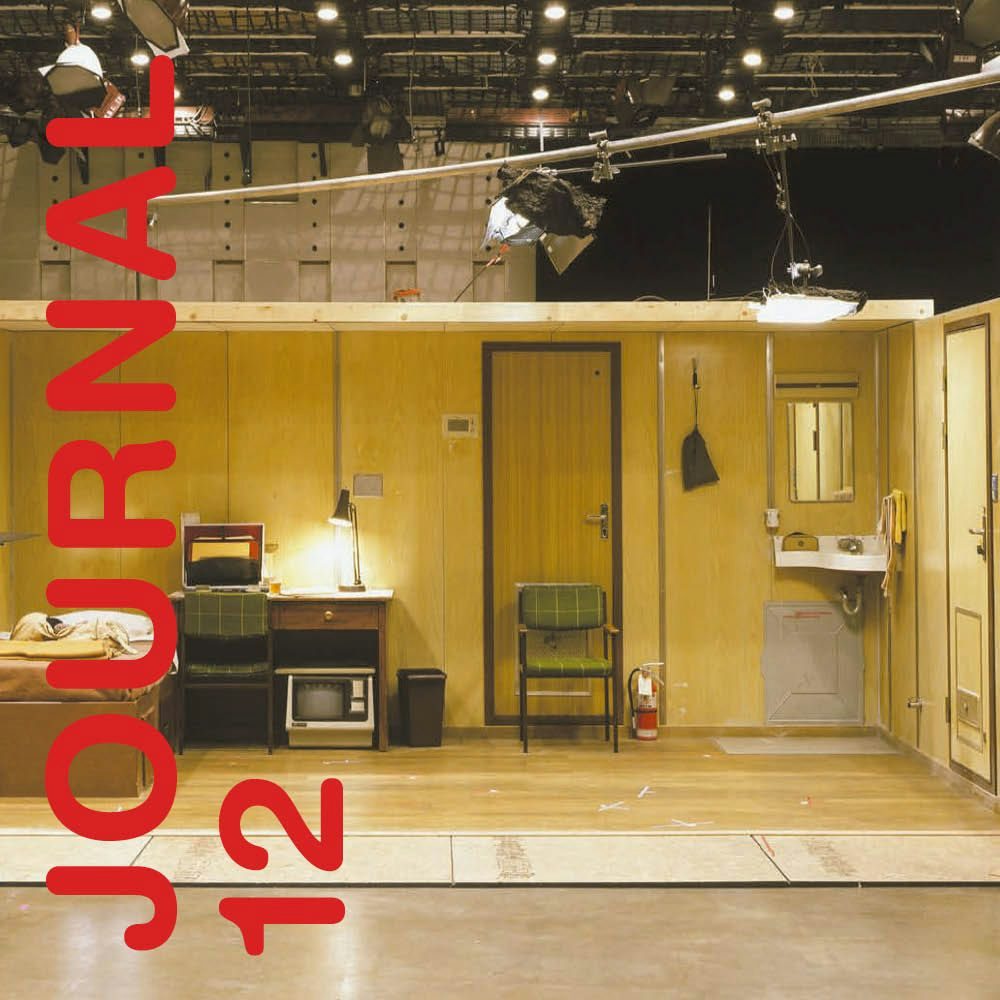

Like these three inaugural bodies of work, within a kind of Canadian photography, the work of the twelve artists in the present exhibition makes visible the real and illusionistic mechanisms involved in the production of photographic space. Their images are thus designed to be the stage upon which both the ways of making and the ways of thinking space, whether that space is realistic or improbable, are made visible. The places where these photographers have chosen to work are good indications of this. Whether they create their images in the studio or on location—cities, gardens, landscapes, museums, laboratories, theme parks, or workplaces—most of these places are already “set-up.” The images thus allow us to become aware of these settings and to question their role in the production of meaning or ideology. For all of the artists in this exhibition, it seems, the scene is as important as the space seen, and the construction of space is as interesting as—if not more than—that which is apparently being described.