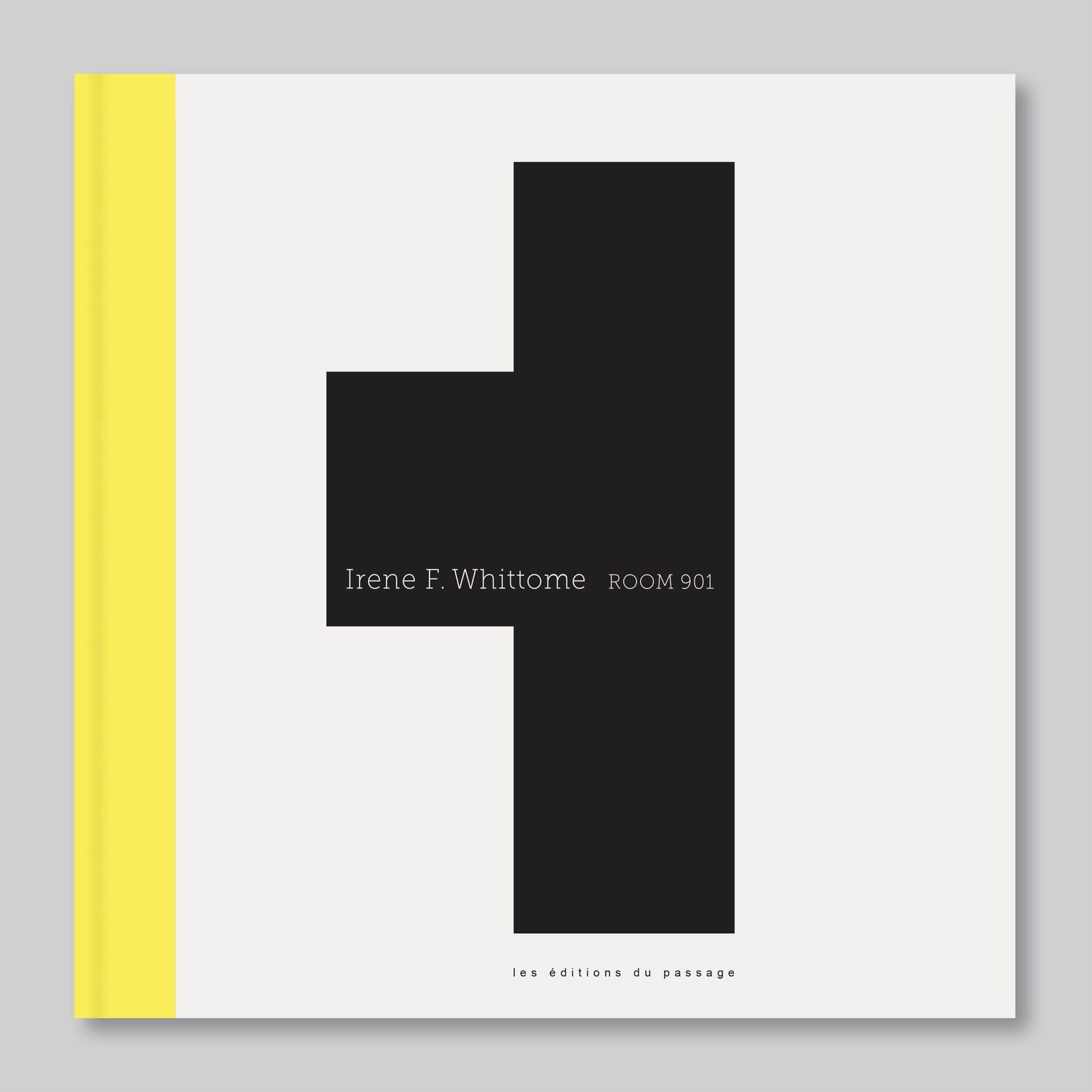

Irene F. Whittome

Room 901

2013.01.25 - 09.03

Irene F. Whittome. Room 901: 1982, 1983, 2013

MARIE J. JEAN

Room 901 is a vast undertaking that led Irene F. Whittome to work in her studio for two consecutive years, creating a work and systematically documenting its production. The enterprise resulted in more than 1,500 photographs, a 16mm film, several boxes cum display cases, and three exhibitions. Thirty years later, Room 901 is the subject of a reflection on the modalities for re-enactment of a site-specific intervention, and provides the opportunity to examine the variable status of a work, its documentation and its exhibitions.

During the summer of 1980, Irene F. Whittome finalized a series of installations to be shown at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Her studio was emptied as a result, and she began creating Room 901. Anything left in the studio was stacked in a corner; the brick walls and columns were repainted in white. The space was prepared in the same way a painter primes a canvas before coating it with pigments. The studio on Saint-Alexandre St. then became the medium for a site-specific process that evolved from October 1980 to July 1982. Whittome’s action at the site would be essentially pictorial in nature, though complemented by arrangements of objects. On the wall adjacent to the arched windows, she painted a figure, which through its many stages of modification tended to resemble a cross: a black square on white background, a white band on grey background, a white square on grey background, a shortened cross on white background and, finally, a black cross on white background. That elementary formal vocabulary immediately calls to mind the pictorial research of Kazimir Malevich, though in the two cases the causal chains are quite different. Whittome reproduced minimalist shapes that she changed every day over the course of more than six hundred days, while documenting them under various lighting conditions. The film and the hundreds of photographs are documents of the time the artist spent working in her studio in this manner. But unlike what this method of documentation heralds, the images do not show the process of production, in which the work might be seen in an unresolved, or incomplete, state. Quite the contrary: they were made to document a succession of pictorial compositions, each of them quite fully developed.

In 1982, Whittome was invited by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal to reconstitute Room 901 as part of the group exhibition Repères. Instead, she decided to show the results of her work in three different spaces: the film 901 / le 4 juillet 1982 was projected in the museum’s freight elevator; seven photographs from the Saint-Alexandre series (1980–82) and twenty-two boxes from the La Gauchetière series (1980–82) were presented at Galerie Yajima in Montreal; the artist’s studio on Saint-Alexandre St. was opened to the public;1 and a communiqué was produced, connecting the three simultaneous events. That fragmentation into three destinations with distinct functions (studio, commercial gallery, and museum) bore witness to three moments in the life of a work of art (production, commercialization, institutionalization). A year later, in 1983, the artist presented Room 901 in an institutional context, describing the new exhibition as a “Re-enactment.”2 In the catalogue to that exhibition, Jacqueline Fry wrote: “The neutral spaces of the Alberta College of Art Gallery will receive the memory of a place the public will not have explored in its definitive aspect, but the indications of the aesthetic adventure it witnessed will be there.”3 Already in 1983, both the artist and the author thus drew our attention to the issues surrounding the repeated re-exhibitions and remediations of Room 901 since its conception in 1980.

It is not possible to show the unshowable—the historical, aesthetic, institutional and subjective contexts in which a work (re)appears every time it is re-enacted; at best, one can show the traces, the clues or signs to what these had originally been. True, this generally occurs through the documentation that accompanies an exhibition, but strategies that make present, in the experience of the work, that process of historicizing and visualizing the past also need to be elaborated. Indeed, Irene F. Whittome wrote, in the communiqué accompanying the first exhibition of Room 901: “The public presentation of Room 901 marks the end of two years of research and four years of occupancy in Room 901. These works form an integral part of the work and of all of the documentation that, taken together, comprise the Room 901 series.” At the risk of contradicting her, I would add that Room 901 must also comprise all the traces and signs that bear witness to its successive exhibitions, in such a way as to re-invest it with new knowledge and narratives that are unceasingly contributing to the (re)production of its history. This present exhibition, metaphorically set on a pedestal, seeks to investigate and make visible the processes by which a work is thus re-actualized.

1. The composition was finalized in July and remained in that state until October 1982. The decision to open up the studio space to the public may seem paradoxical if placed in relation to the filmic and photographic works acting as its mediators. Yet one must not misconstrue Whittome’s aims: she opened up her studio to allow the public to experience, in the phenomenological sense, her pictorial intervention at the site of its creation.

2. Jacqueline Fry, Irene Whittome, 1980–82 (Calgary: Alberta College of Art Gallery, 1983), p. 33.

3. Fry, p. 19.

Galerie Simon Blais, Occurrence, espace d’art et d’essai contemporains, and VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine invite you to an event in three spaces, providing an opportunity to discover little-known bodies of work by Irene F. Whittome. On the same occasion, Les éditions du passage will launch a monograph devoted to the artist, produced in partnership with VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine.

AFTERMATH

SIMON BLAIS, FROM JANUARY 16 TO FEBRARY 23, 2013

CLAUDINE ROGER

In the late 1970s, Irene F. Whittome’s practice shifted from moulded paper shapes to works in wax, which would emerge as one of her favoured materials. She coated found objects as well as cardboard and wood-plank constructions in encaustic (coloured pigments fused with wax and turpentine). The painstaking method of application, combined with a natural process (the encaustic-encased volumes were exposed to daylight) allowed the artist to achieve textures and colours reminiscent of a true aged patina and to fix, via a process of stratification, various experiences lived in the past, present and future. In 1980, the artist began employing encaustic and coloured pigments more intensively, creating a new series of painting-objects. Consisting of agglomerations of paper, doors, panels and cardboard coated in wax with black and white pigments, these pieces, entitled Encaustics, were shown at Galerie Yajima, Montréal, in 1980 and then incorporated into the re-enactment of Room 901 at the Alberta College of Art, Calgary, in 1983. They will be shown again along with selected works from the Room 901 series at Galerie Simon Blais, as part of the exhibition Aftermath.

BESTIAIRE

OCCURENCE, FROM JANUARY 19 TO MARCH 2, 2013

MONA HAKIM

This imposing corpus of works, comprising biomorphic and archetypal figures, follows from Whittome’s expressionist drawings from the years 1963 to 1967. The paintings, striking in their very large vertical format, exacerbated colours and textures, wild and aggressive iconography, and in the artist’s impassioned gestures, easily imagined, point not only to a significant formative period in Whittome’s creative action, but also to a revelatory moment in her artistic journey and the evolution of her work. These bodies, half-human, half-animal, larger than life, with their embowed skeletons and webbed extremities, evoking terrifying insects, immerse us in a disturbing world, at once archaic and mythological.The exceptionally little-known Bestiary corpus, which is comprised of fifteen paintings – eight very large-scale canvases and a series of portraits, has for its part never been presented in its entirety, and is now being shown in this first-time exhibition at the Occurrence Gallery.