Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn. Space Fiction & the Archives

2012.11.02 - 12.15

LIZ PARK

The year was 1967. The space race between the United States and the USSR was escalating concomitantly with the intensifying Cold War and the nuclear arms race. Across the Pacific in Southeast Asia, the US was embroiled in a hot war in Vietnam. Meanwhile, the Civil Rights movement was in full force and there were increasingly restive voices that eventually climaxed in worldwide student protest movements in 1968. In contrast, Canada was under-going a period of euphoria. Celebrating its 100th birthday, the young nation saw centennial projects sprout in cities and towns, big and small, across the vast stretch of land. Most famously, Montreal hosted Expo 67, with the exhibition theme of “Man and His World.” Much more modest in scale but equal in enthusiasm was the centennial project of a small town of 3,500 residents—St. Paul, Alberta.

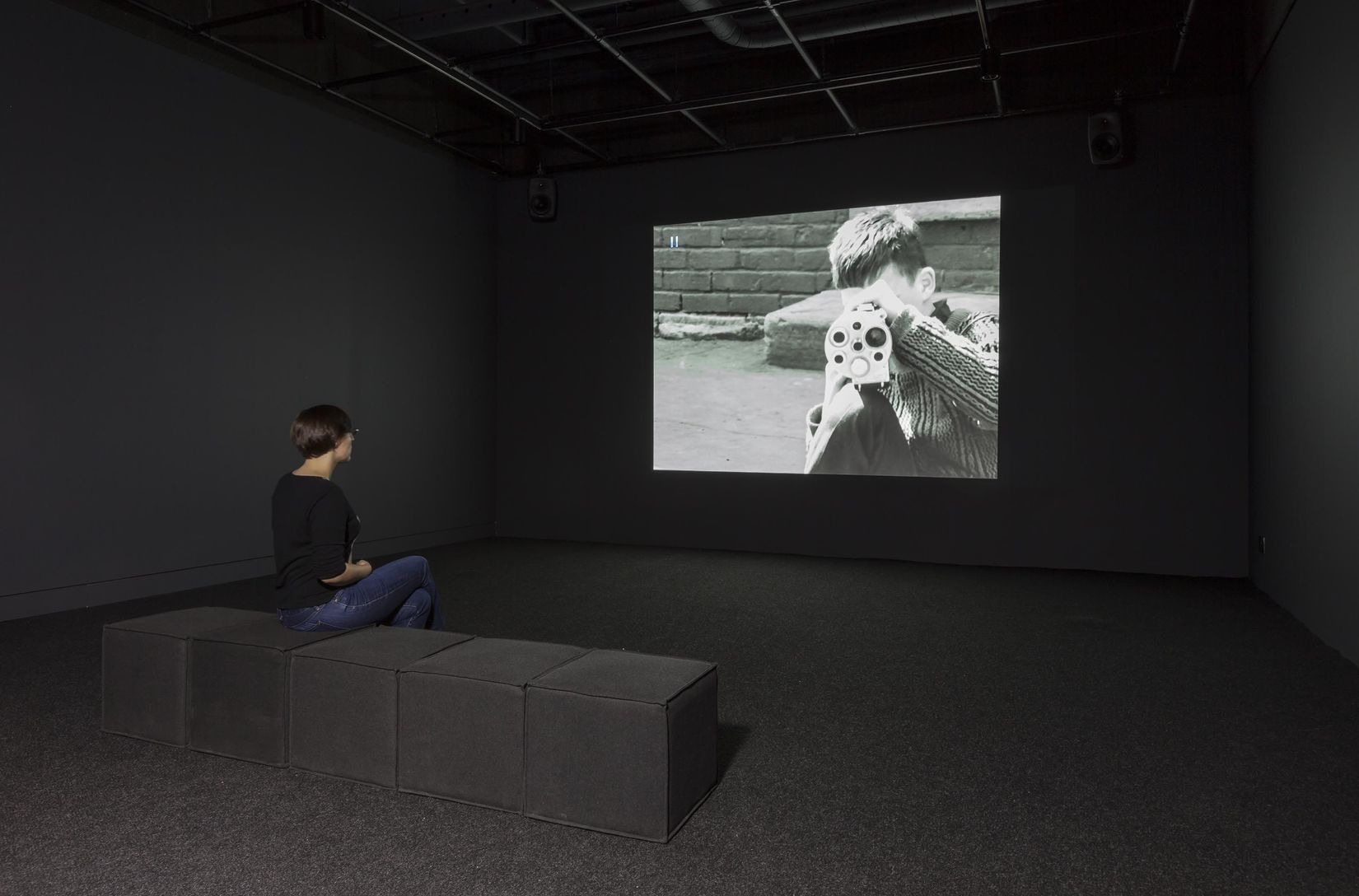

This exhibition by Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn is a time portal that transports us to St. Paul in 1967 via two main elements : a “space fiction” in the form of a video entitled 1967: A People Kind of Place, and an archive of reproduced materials ranging from postcards to news-paper articles to an aerial photograph. They both convey the sense of optimism and enthusiasm for the national coming-of-age in this small town proclaimed the “Centennial Star of Canada.” Its shining achievement was the construction of the world’s first “UFO Landing Pad.” Approximately 30 feet by 40 feet along its elliptical axes and 8 feet in height, the pad is conspicuously insignificant in size, as confirmed by the difficulty of locating it on the aerial photograph of the town included in the archive. Of course, this was not a real touchdown site for intergalactic vehicles. Declared a “symbol of Western hospitality” by Paul Hellyer, then Minister of National Defence, who gave a speech at its inauguration ceremony, the landing pad was just that—a symbol. However, the adjective that describes the kind of hospitality that it represents deserves closer scrutiny in the context of 1967, the year of a significant change in immigration regulations in Canada.

Replacing the blatantly exclusionary Immigration Act of 1919, which weeded out people from specific regions and racial or religious backgrounds, the new point-based system introduced in 1967 evaluated the qualifications of a potential immigrant based on language skills as well as educational and professional experiences. Although trumpeted as an objective mechanism set in place to ensure fair opportunity, the point system in actuality measures the potential immigrant’s ability to effectively participate in a particular Western model of democratic political-economy. It would be extremely naïve to assume that a positive outcome from this assessment translates directly into to a newcomer’s fulfilling and satisfying participation in Canadian society. Yet, the feverish welcoming of all, both terrestrial and extra-terrestrial, to St. Paul points to the infectious spirit of multiculturalism as an identity-defining ideal of Canada.

The purpose of Nguyễn’s video and the archive is not to simply critique the naïveté of a small-town centenary project. Nor is it out of nostalgia for the past’s utopian impulse. In combining the fact-based archive with what the artist calls “space fiction,” she opens up a gap through which questions and doubts can emerge. A space fiction rather than a science fiction, the video draws attention to St. Paul as a space of contact and settlement from where the national narratives have written out its original inhabitants—in the same way “Métis” was dropped from the town’s older name St. Paul des Métis or in the same way the nearby Blue Quills Indian Residential School students performing a play called Hello World in 1967 represented different nationalities but excluded indigenous nations. Nguyễn’s video starts with a title card that reads “This is a true story.” With the Latin root of the word “fiction” meaning “to shape” and “to mould,” her space fiction does not necessarily try to replace one story with another, but gestures toward how spaces of future encounters can be shaped differently.

Fast-forwarding ahead, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared the failure of multiculturalism in 2010. A Norwegian gunman massacred 77 people in Oslo in an anti-Muslim bombing and shooting in 2011. Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy incited the rage of the right-wing faction by saying, during the 2012 presidential election campaign, that there were too many foreigners in his country. These events lay bare the limits and impasses of multicultural state policy that is imposed and managed in terms of integrated uniformity. Looking back at 1967 with the insight of the present day, the optimism of the people of St. Paul and Canada takes on a more nuanced tenor.

In the late-1960s context of intense global conflict, opposition and activism, exploration of the “final frontier” was shaded by the warring ideologies of the space race even as it held promises for a better future. Belief in peaceful co-existence with the unknown other, which characterizes the UFO Landing Pad, was an antithetical stance to the long and violent war in Vietnam. From this broader perspective, St. Paul is a curious case study of contradictions and complexities : of how a small group of people imagined their home at an important moment in history in Canada and beyond. Space Fiction & the Archives looks at St. Paul macroscopically, as a space of incongruities and optimism from where a new set of vocabulary around belonging and co-existence, and the will to imagine a different geography of encounters, can emerge.