Kelly Mark

Stupid Heaven

2008.09.06 - 10.18

BARBARA FISCHER

Among the shelves stacked with CDs, books and bottles of scotch, a punch clock flashes up and rings with a hard clang in one-hour intervals. The visitor is in Kelly Mark’s studio, and In and Out is the monumentally conceived evidence of her work. Hundreds of time cards, stacked up in steel racks, bear the stamps of the time that Kelly Mark has punched in and out of work as an artist. Each rack comprises the weekly logs for one year—from 1997 to the present (and pledged to go beyond). In proto-conceptual manner, In and Out commits artistic creativity to mechanical process, biography to administrative system, and life to “file.”

Over several years now, Kelly Mark has been concerned with time. In and Out, with its indexical preoccupation, mimics industrial or service sector—type human-resource tracking methods. But the records show nothing resembling a nine-to-five occupation. Measuring the capricious durations of the working life of an artist, In and Out’s hardcore conceptualist format, that grey-in-grey of the file, unexpectedly returns something of the unpredictability of “life.” In fact, the tension between formal methods of time management and the interest in duration (the way in which, in an ongoing complex moment, life actually feels lived) underlies much of Kelly Mark’s interests.

In some of the early works Kelly Mark would set up a task to follow it through methodically, echoing an industrial mode that found its appropriate counterpoint in the concerns of minimalism, process art and conceptualism. Here the idea is a machine, such as in a series of drawings made by setting a graphite pencil to paper and drawing tight spiralling circles until the graphite was gone. The material is consumed by mechanical execution, and the artist’s time is its aura.

More recently, Kelly Mark’s focus has shifted from the tautological nature of “a work made by time spent working” to frame the poignant actions of others and the residual flotsam of the everyday, instead. The conceptual format becomes an indexical medium, taking account of a particular, observed phenomenon—whether repetitious or unpredictable in nature. A series of photographs reports on the way in which desperate people have affixed, with great ingenuity and creativity, comedic notices on broken parking meters, seeking to avert ticketing. Notably, the new, more efficient sun-powered devices now in operation everywhere no longer allow for grey zones of freedom granted by mechanical failure. The administration of time has hardened its grip, and creative forms of “talk-back” have disappeared.

Kelly Mark’s work demonstrates low-key attitude and slow-burning resistance to the abstract administration of time, registered precisely within its system. Sometimes, suspension in the automaton of a task, the absorption within it, suggests a preferred mode of being—the task that requires no thought at all allows thought to take its own course. Within the stupid there lies heaven. At other times, Kelly Mark’s work seeks to terminate tasks that are obsessive in the focus on achievement—which is perhaps the very same thing. For a while her work concerned itself obsessively with the incomplete sentence “I really should. . .” Indexing the innumerable ways that define what one indeed should do, an audio track spells out the contents of I.R.S. to the point of sheer excess. If obligation is bound up in social structures (family, health, work), to refuse it (by procrastination or resistance) casts doubt on their values and diligent striving. Such existentialism underlies much of Kelly Mark’s humour, as when an orchestrated demonstration puts an end to the historical, conventional form of social demands: in front of a gallery’s black-tie fundraising event, a group of artist friends bearing blank placards declare, “What do we want? Nothing!”. . . “When do we want it? Whenever”. . . and “Hell no. We don’t know.”

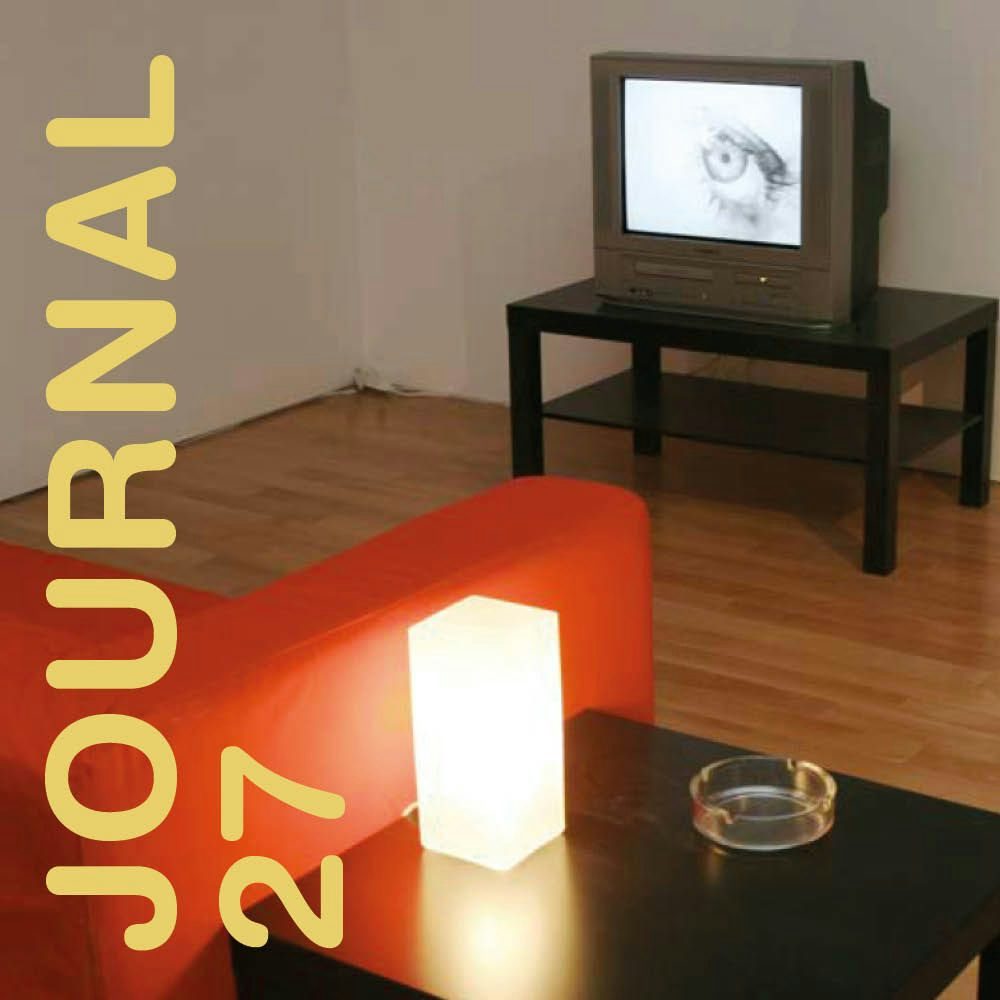

Watching television is perhaps the greatest means of contemporary distraction and procrastination. It is also the greatest tool of time management and immersive pleasure ever devised. If television constructs and dominates “free” time, it has substantially altered the once “natural” pulse of day and night, waking and sleeping, by absorbing its audience into an interstitial day-dreaming, time-eating, surreal time. After being concerned with the glow of television for a while, Kelly Mark’s new installation, titled REM1 is nothing short of a tour de force, featuring a movie that illuminates the experience of channel-surfing television time. An encyclopedic array of segments of movies taped off television is edited and strung together into a new, two-hour-and-sixteen-minute “thriller” complete with title, warnings, ads, network logos and credits. The story follows a protagonist who seeks to escape the law, and who changes shape like an avatar, appearing with each edit in the body of a different actor. He (and through him the audience) perpetually loses and regains track of where he is—whether in a dream, asleep, awake or in a drug-induced state. These states are not only the means of narrative propulsion and the content of the new film; they also elucidate the subject of television as such: consciousness recycles and strings together changing attention spans and pursuits in a combination of narrative bits. The meshing of production and consumption in narrative hyper-time informs a new sense of subjectivity and artistic practice.