Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box

2008.11.06 - 12.13

An Undertaking to Preserve Flashes of Brilliance

MARIE J. JEAN

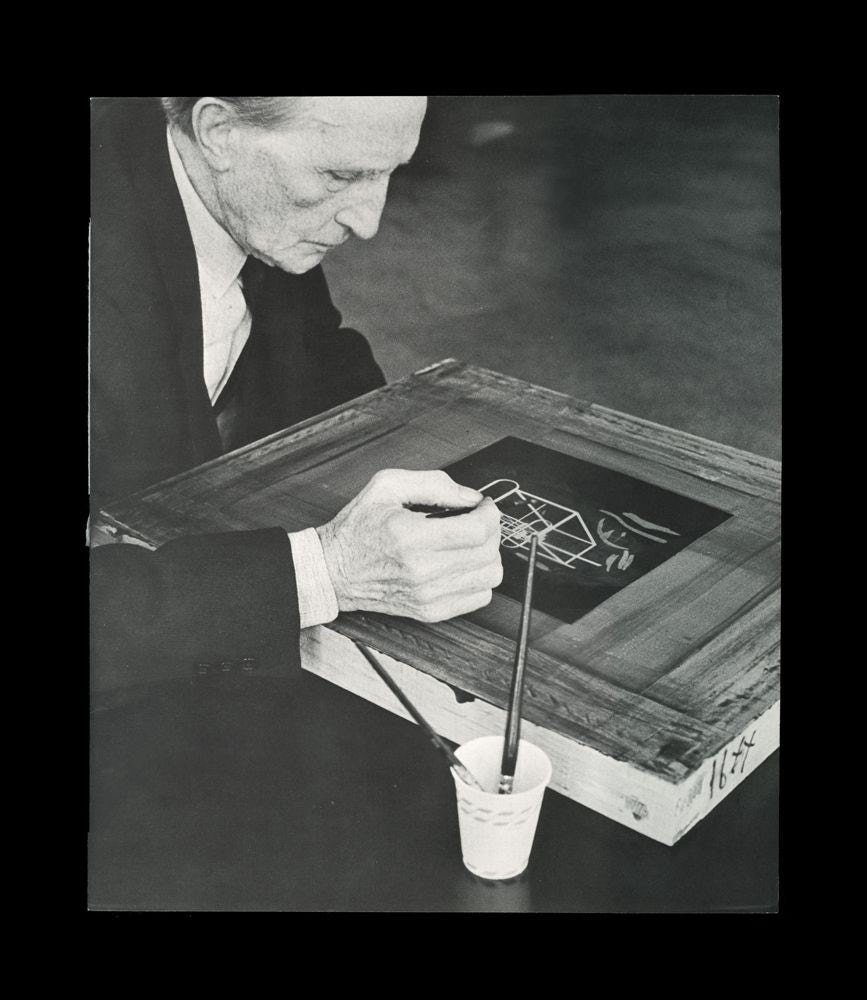

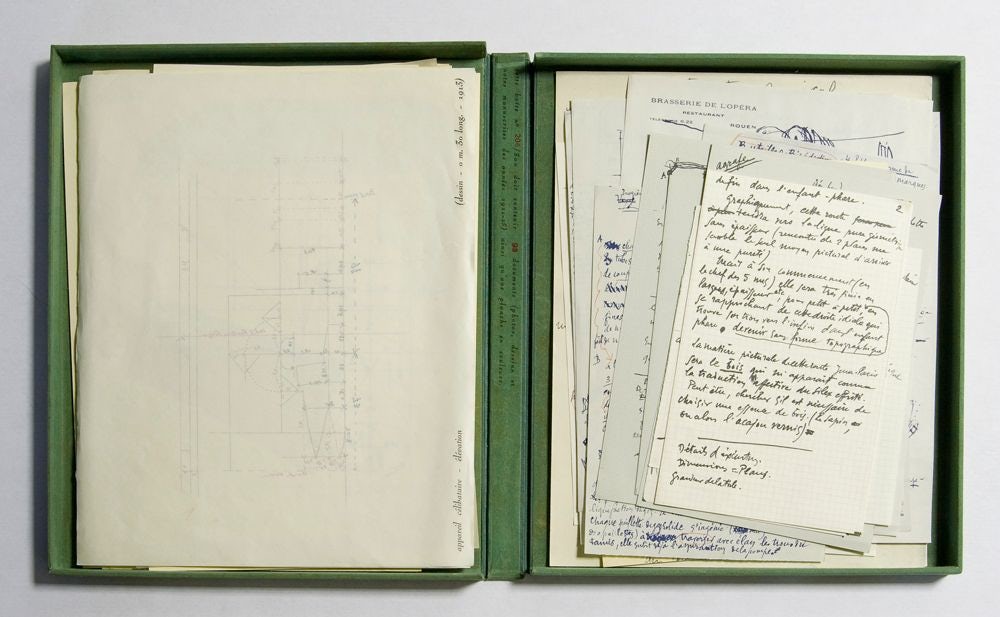

To open the Green Box is to access ninety-three notes, sketches and documents—often no more than simple slips of paper—that helped sustain the ideas and conjectures that led to the creation of one of the most fascinating works of the 20th century: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even. “Every time an idea came to me,” Marcel Duchamp explained, “I would write it down on paper; I would let it simmer. Like that, for eight years. Not all day long: twenty minutes here, twenty minutes there. But still, eight years.”1 Duchamp’s undertaking—determined by his desire to ascribe primacy to the conceptual dimension of the artist’s work—was a long process that did not end with the publication of his Green Box in 1934. It ushered in an era: henceforth, the idea in and of itself became a work.

The Notes became hugely significant to Duchamp and, as early as 1914, he hit upon the idea of producing a facsimile version: “I wanted to reconstitute them as accurately as possible,” he said. “I had lithographs made of all these thoughts, using the same ink as the originals. To find exactly identical paper stock, I had to rummage throughout the most unlikely corners of Paris. Then I cut out three hundred copies of each litho, using zinc stencils that I had fashioned after the contours of the original papers. It was a lot of work, and I had to hire my concierge. . . .”2 The goal of this attention to detail and mimicry was to preserve the original state in which these thoughts had come to him. It speaks to Duchamp’s constant desire to assemble and preserve his works.

Duchamp began The Bride in 1915, but worked on it until 1923, when he left it in its “definitively unfinished” state. The Notes he wrote throughout the production of the work, he explained, were “designed to complement the visual experience as in the manner of a guide.”3 But one must not be fooled by them: the share of mystery contained in the work is also contained in the Notes. They nonetheless have the advantage of opening holes in the mind of the reader-spectator without ever exhausting secrecy: exploring The Bride’s secrets depends on the searcher’s ability to construct its riddles using logic comparable to that of its creator. To achieve that logic one must draw from Stéphane Mallarmé spatial semanticism, Raymond Roussel’s mechanical line of thinking, and Henri Poincaré’s four-dimensional space-time.

VOX is thus delighted to open Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box for our audiences, making available a work that is celebrated, yet little known, and offering a wonderful opportunity for exchange and discussion of the issues it raises. Its exhibition would have been impossible had it not been for the artist and impassioned collector Bill Vazan agreeing to loan it to us. We express our gratitude to him for doing so.