Michael Blum

War and Peace

2014.02.07 - 04.12

Since the early 1990s, Michael Blum has created a body of work that probes the question of History in its relationship to narratives constructed, recomposed and reinscribed in the present. He explores forgotten, sometimes controversial (hi)stories and personalities—such as the encounter of Hitler and Wittgenstein in Linz and the influence of the feminist Safiye Behar on Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the Republic of Turkey—materializing them in museum, monument or documentary form. His methodology is that of investigation, and is grounded in extensive research conducted in varied cultural and political contexts.

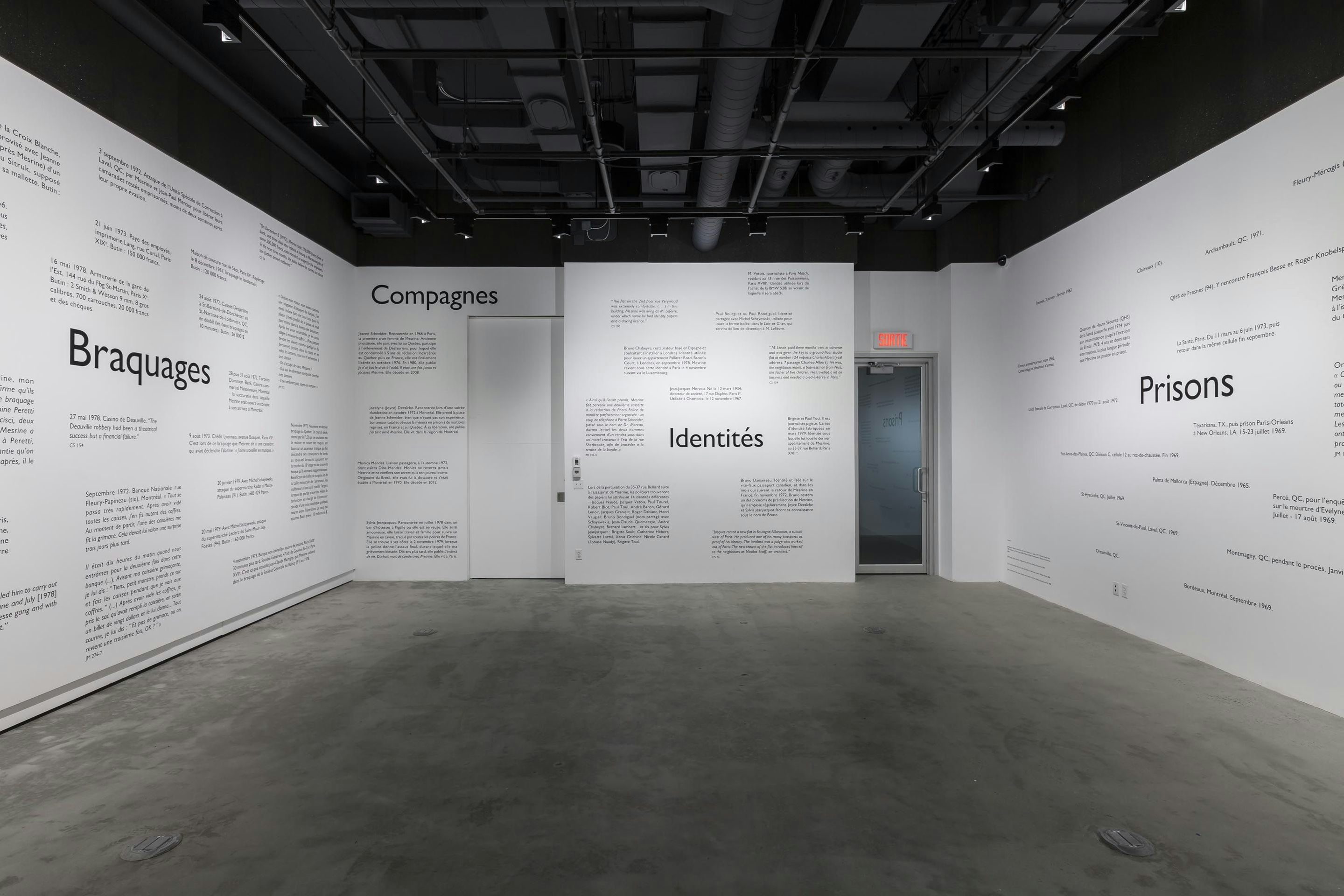

War and Peace, Blum’s latest solo exhibition, comprises an installation and film that recount infamous French criminal Jacques Mesrine’s time on the run in Canada in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Punctuated by interviews from which a living, collective memory emerges, the film retraces Mesrine’s activities in Montreal and the Gaspé using a narrative with cinéma vérité accents.

Although this major figure of modern crime has been portrayed in many books and films, his Canadian spree has been given short shrift until now.

WILL STRAW

The story of Jacques Mesrine’s time in Quebec, from 1968 to 1972, circulates within popular memory in jumpy and episodic form. Mesrine’s stay here was punctuated by bank robberies, a kidnapping, prison breaks and rescues, flight to the U.S., and a trial for murder in Gaspésie. With time, the sequence of these events has become hazy, and the threads connecting them are easily lost amidst the busy drama of a period sometimes considered Quebec’s Golden Age of outlaw crime. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, robber/adventurers like Mesrine, working with only a handful of accomplices, had largely displaced the business-like syndicates who typified Quebec criminality in the 1940s and 1950s. Mesrine arrived in Quebec the year after Monica la Mitraille (“Machine-Gun Molly”) was shot to death following a string of spectacular bank robberies in the Montreal area. Monica la Mitraille and Jacques Mesrine—like Bonnie and Clyde, subjects of one of the top film successes of 1968—would become folk heroes in an era in which robbery and flight from the law had come to stand for youthful rebellion.

During Mesrine’s years in Quebec, local crime tabloids like Allô Police and Photo Police were filled with grim photographs of criminal hideouts in Montreal’s suburbs and mug-shot portraits of criminals, mostly white and male, who were slowly adopting the long hair and sideburns of the countercultural figures who came to dominate popular culture. This was also a period in which crime and politics became interwoven ever more tightly, in Quebec as elsewhere in the world. Robbery had come a popular means for underground political movements, like the Front de liberation du Québec, to raise funds to support their causes. In jails like the Unité speciale de correction in Laval, from which Mesrine escaped in 1972, the demands of the incarcerated for better conditions and treatment joined up with broader movements for prison reform. It was difficult, as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, to draw a sharp line between crime and revolution.

Michael Blum’s film Cavale au Canada, which is at the centre of the installation War and Peace, revisits many of the key sites and spaces of Jacques Mesrine’s time in Quebec. Some of these spaces, like the apartment on Sherbrooke St. East or the suburban mansion in Mont-Saint-Hilaire—both of which Mesrine occupied in 1969—are described in later accounts of his life as spaces of modern luxury. They appear to us now, however, as unattractive, tacky structures. We are unsure, though, whether this difference in opinion expresses our own snobbery towards Mesrine’s lower-middle-class aspirations or a broader, collective shift in taste since the 1960s. In any event, these modern constructions, like the bars and motels built to cater to tourists in Percé, where Mesrine later sought refuge, are full of hopes and ambitions whose sad disappointment the film successfully conveys.

Like other recent film works by Michael Blum, Cavale au Canada follows a biographical narrative which resists the full intelligibility of lives and events. Our narrator presents herself as Mesrine’s unacknowledged daughter, seeking after the truth of her father’s life. As the film travels to Percé, in the Gaspésie region of Quebec, we are drawn into encounters with townspeople who fascinate us in ways which have little to do with their links to events almost half a century old. The interviews, which make up almost two thirds of the film, expose us to local accents and ways of speaking, and in their extended length these conversations offer their own pleasures and interest. We relish the ways in which the older residents of Percé tell their stories, in words which somehow seem both freshly improvised and highly polished through repetition. As viewers, we elaborate our own theories about culpability in the murder of the motel keeper Évelyne Le Bouthillier—a murder of which Mesrine was accused and was eventually acquitted.

While the story of Mesrine’s life has been recounted many times, in books and films, Michael Blum’s War and Peace is the first work to tell this story from a Quebec perspective. As the installation shows us, Mesrine’s séjour in Quebec left its mark on places and personal memories, while his own insolent rebelliousness fit neatly within ascendant political and cultural sensibilities here.