Omer Fast

2007.03.17 - 04.28

MARK GODFREY

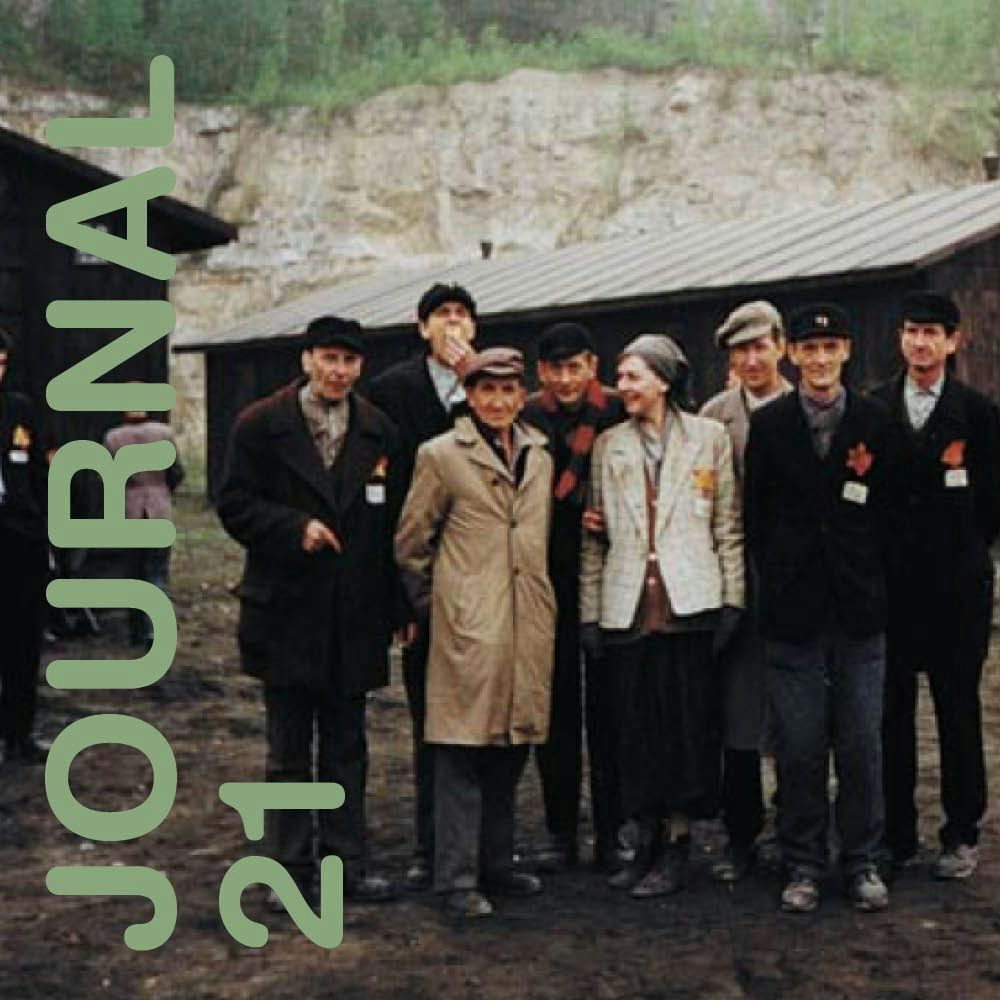

In 2003, Omer Fast travelled to Krakow to research the aftermath of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, ten years after the film was released. He found a burgeoning tourist industry devoted to the film. Tour guides were driving mainly American tourists to the still intact film sets of the concentration camp, as well as taking them to visit Auschwitz. Fast recorded some of these tours and conducted interviews with Poles who, ten years earlier, had been extras in the film. Some described the ways in which potential ‘Jewish’ and ‘Polish’ characters were divided during the auditions. Older extras mingled their memories of the 1940s with their recollections of the early 1990s. All of them, however, recalled the events of 1993, describing their motivations and experiences of acting out scenes

Fast’s footage addressed the Hollywoodisation of the Holocaust, scrutinizing Spielberg’s magnum opus by deploying tactics associated with Claude Lanzmann (Lanzmann had refused to use archival footage or to recreate scenes of the Holocaust when making Shoah (1985), determining instead to forge his encounter with history through interviews with Jewish survivors and Poles who had lived near the camps). The critical bent of Fast’s project was in no way tempered by his acknowledgement that the extras’ experience was real and deserving of serious attention; the artist allowed them to articulate the difficulties of reconstructing such a traumatic event in Polish history. Editing the footage for his two-screen installation Spielberg’s List (2003), Fast made a crucial intervention. Working with a Polish translator, he was made aware of the contingencies of translation in the interviews he had conducted. Reflecting on this, he decided to play identical footage on each screen but to subtitle them with slightly different texts—one referring to the actual events of the 1940s and the other to the film. During some footage of the tour, for instance, one screen is subtitled with the words ‟And the building opposite—there was one of the gates” while on the other screen we read ‟And the building opposite—there was one of the takes.” Fast even employed this device when speakers were English, but when they were Polish, sometimes it became impossible to tell which historical period was being addressed.

The subtitles further compounded the historical confusion and its representation, but it is interesting to note how the strategy operated for viewers in the screening environment. With two screens before them, and with complex material unfolding at a pace, it was initially impossible to understand what was going on. At first, all that could be sensed was a flickering difference on the peripheries of the two screens. The contrast between the subtitles registered more in terms of divergent shapes than alternative translations. Only later, with repetition, could the viewer guess the tactic at work. Fast’s device emphasized our incapacity to fully apprehend a work in the first encounter, while encouraging us to pay attention to the fickleness of subtitles—an aspect of the video image we might usually take for granted—and to choose between the two meanings.

Spielberg’s List exposes the complexity of Fast’s project: it addresses the information presented through film and TV, and exposes the manner in which it is delivered. By attending to aspects of the image such as the subtitle and the soundtrack, Fast sheds light on the subtle ways in which meanings are disseminated. Sometimes he has used tactics of insertion as well as interruption. In 2001, he obtained copies of The Terminator (1984) from New York video outlets, and he overdubbed some of the most brutal and silent scenes in the film with sections of dialogue that he had taped in which adults recollected their violent childhood memories. The videos were returned to the rental shops to await the next, unsuspecting customers whose Schwarzeneggerian fantasies would be interrupted by a sour dose of the real. If his strategies here owed much to Cildo Meireles, elsewhere, in a mammoth act of manipulation, Fast updated Richard Serra’s savage articulation of TV’s commercialism, Television Delivers People (1973). Through 2001, Fast recorded hundreds of hours of CNN presenters speaking directly to camera. He fed the footage into a computer and cut it up into words and syllables. From this database, he constructed an 18-minute monologue, CNN Concatenated, which is delivered word by word in a fast, jolting fashion, by individual news presenters. Just as Serra’s rolling titles spoke directly to their readers (“You are delivered to the advertiser who is the customer”), Fast’s presenters address their viewer, “Look, I know that you’re scared…,” indirectly admitting the manner in which news programs both foster and feed off the neuroses of their audiences. As well as being incisive, the work is also very funny. The slick and slimy anchors are made to utter sentiments quite beyond their sensibilities, but appear absolutely unruffled, their manicures and fake tans always immaculate.

Fast’s most recent project is Godville (2005). He made the work at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, the living-history museum where visitors can talk to various staff members who are dressed as 18th century characters and who represent different facets of colonial American life. Fast interviewed and filmed the costumed staff when they were in character, but also out of character, as they spoke about their motivations for working and living at the museum. If such places can sometimes encourage what Fast called a ”pornography of the past,” he disrupted the illusion by confronting the characters as 21st century individuals. As might be expected, various other forms of disruption take place in the work. Fast chopped up the interviews and re-assembled words—if the viewer is initially unsure whether the speaker is talking in or out of character, after a while it is impossible to gauge whether the monologues correspond at all to the actual recorded interviews. Although such confusion is in some ways appropriate to the temporal confusion of the interviewees and museum visitors, what is exemplary about Fast’s approach is that the final product does not gel into some spectacular reconfigured whole (think of Candice Breitz’s recent use of splicing). His Brechtian interruptions genuinely interfere with the coherence of the subject matter, providing space for critical thought.

The installation requirements of Godville enact another cut: the work com-prises two films projected onto a single floating screen, in the manner of Michael Snow’s Two Sides to Every Story (1974). On one side of the screen, we watch the chopped up interviews; on the other, Fast plays footage of the museum and of its actor-employees’ houses. At times it is hard to distinguish the genuine colonial buildings from the 21st century dwellings—such are the actors’ tastes for period kitsch. The footage segues into shots of recent constructions of faux 18th century houses, a passage that recalls a kind of updated Homes for America in which Dan Graham’s 1960s minimalist forms make way for 21st-century traditionalism. While economically representing the human and architectural aspects of Colonial Williamsburg, the two films equally complement and interrupt one another. Watching either side of the screen, viewers can feel distracted, realizing they are missing the footage playing on the reverse.

Godville ends on one side of the screen with a medley of images of Southern churches while on the other, Fast’s edit is of an African American actor who intones countless sayings about what God means to him. Fast seems to view the increasing religiosity of the South as an end result of the nostalgia often perpetuated by institutions like Colonial Williamsburg, even though his research indicated that Colonial Williamsburg was not monolithic. Indeed, he discovered that there have been times when the museum has put history to work in an almost Benjaminian manner, as, for instance, when one day an estate auction was re-enacted and visitors to the tourist attraction en-countered the sale of families of slaves. When he conducted his interviews, Fast also discovered that some of the actors were inflecting their performances to reflect their criticism of the current American administration. Playing colonial British subjects questioning their allegiance to the crown, they hoped that inquisitive viewers might draw parallels to the present situation of American subjects. Knowing that the actor-employees had diverse political affiliations that weren’t circumscribed by the museum’s overarching ideology, Fast decided to complicate things further. At some point in their fractured monologues, the interviewees begin to speak back to the camera, accusing Fast of manipulating their words. They complain that he is turning them into stereotypes and ask him what all his editing and studio trickery can possibly accomplish. Of course, it is impossible to know whether or not Fast was addressed this way by the museum’s actor-employees, but by twisting their words, Fast articulates within the project the most severe criticism Godville could possibly attract. As much as Fast questions the spectacular ways in which the culture industry presents history today, he also scrutinizes the facilities of his practice and the ethics of his own art’s criticality.