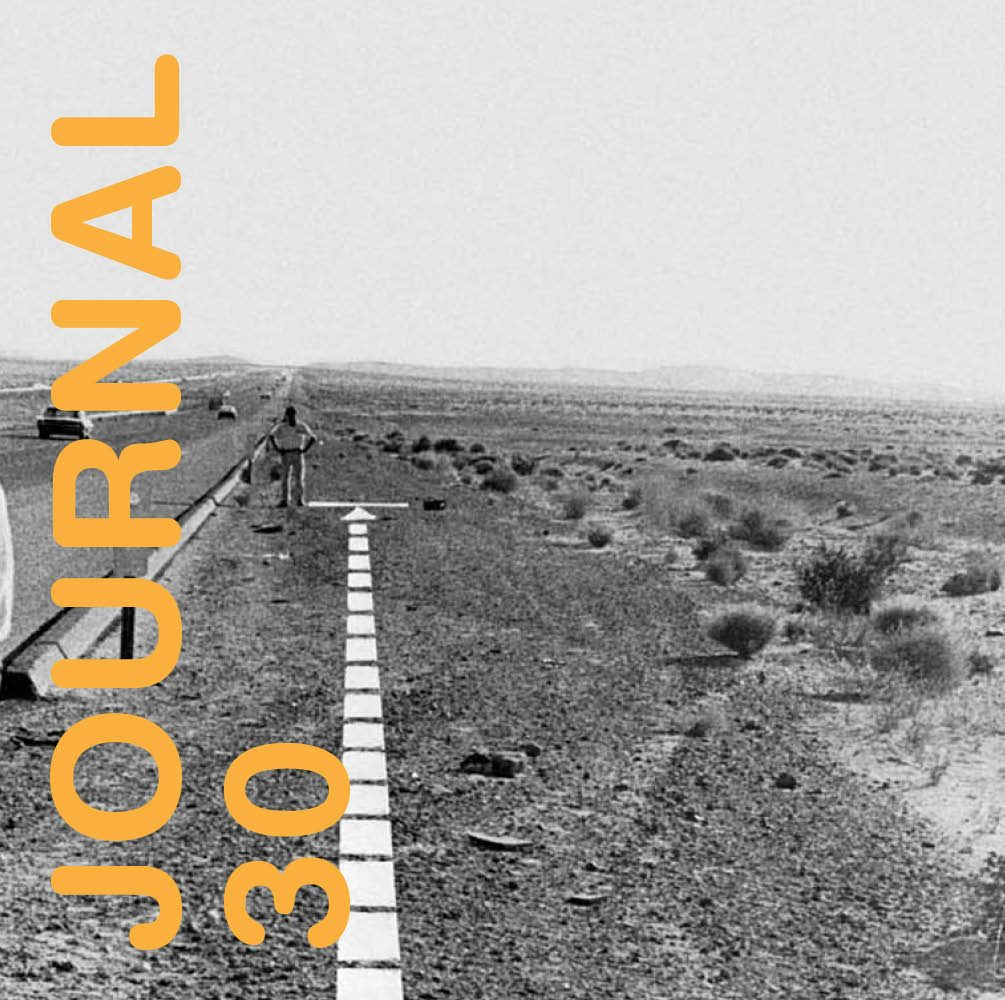

Road Runners

2009.03.06 - 05.30

MARIE J. JEAN

The road and the automobile are subjects and objects of major literary, cinematic and artistic works that laid the foundations of a cross-disciplinary genre—one which continues to evolve. The crystallization of that genre, here designated by the term “Road Runners,” came during the 1950s and 1960s with the publishing of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road,1 Tony Smith’s account of his aesthetic experience on a highway,2 and the release of the Dennis Hopper film Easy Rider.3 Though the Road Runner may be characterized by diverse attitudes and motivations, the road and the automobile have generated new modes of representation and perception, in one or another of these forms. For Kerouac and Hopper, the car and the motorcycle promised complete freedom and mobility, while the road was paved with the ideals of their respective generations. Paradoxically, though, their protagonists learned on their “trips” (in both senses of the word) that freedom remains a far-off goal: what matters isn’t so much the final destination as the “getting there”—a constant progression toward an ideal place. Kerouac and Hopper proceeded from the same starting point: the wanderings of individuals who chose to live by their wits and thus came to face a new conception of reality. But while in film and literature the road runner’s motivation is often an identity quest that sets him or her in motion, in response to a need for escape, a desire for vision and revelation, the artist’s wanderings are introspective—immobile, even.

On the road, time tends to become secondary, abstract—leading to a floating state that makes it easier to retreat into the mindscape. This state is a particularly fertile one, within which ideas can take shape. No doubt it was the state sought by Raymond Roussel, the first writer to literally work “on the road”: in 1925 he designed and had built for him a practical, luxurious trailer, to satisfy his need to move. For writers and for many artists, the automobile represented a singular space for creation that led them to produce significant works – and on occasion, to a new conception of art. As when Marcel Duchamp, dazzled by the brightness of onrushing headlights on a 1912 road trip between the Jura and Paris, hit upon the idea for his “beacon-child” of the 20th century: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. In the early 1950s, Tony Smith arrived at a staggering redefinition of art when he went for a night ride along the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike, without signs or lighting. He had an “unstructured” experience of the landscape, which he could not frame or transform into an art work because it remained forever immaterial. These narratives ushered in a new relationship to art in which the art object was deconstructed, giving way to a new paradigm wherein the conceptual dimension and the experienced event were most important.

Beginning in the late 1960s, that paradigm engendered countless works whose structure was informed by the road, with the car functioning as a moving atelier—with the driver watching the world roll by, continuously, on the screens that are its windows. The framing of those road-images is often doubled by the tighter frame of the car windows, and onto the observed landscape are superimposed reflected views in the windshield and rear-view mirrors. This way of seeing the world, widespread in North America, and especially in Canada, was to exert a huge influence on several Conceptual artists, who used photography to record it. The very act of seeing, previously perceived as something transparent, became the subject of their art.

The history of photography is also replete with road runners, who along the way have produced a register of ongoing urban and social transformations in North America. Photographers are especially attracted to the non-spaces characteristic of American landscapes, focusing their attention on transitional spaces (motels, restaurants, gas stations) and arteries of communication (roads, crossroads, highways, boulevards). Jean Baudrillard made such a road trip in the mid-1980s, documenting his vision of America (Montreal included), and writing a book that expounded upon the philosophical concepts undergirding it. That experiment made manifest the repetitive effect of America’s roads, where the same setting seems to unfold, kilometre after kilometre. A comparable impression was related by Vladimir Nabokov, in Lolita: “By putting the geography of United States into motion, I did my best for hours on end to give her [Lolita] the impression of ‘going places’, of rolling on to some definite destination, to some unusual delight. […] Voraciously we consumed those long high-ways, in rapt silence we glided over their glossy black dance floors.” “But movement brings no progress. Arid hopelessness is all that remains.”4

In the 1980s, image production on the road became animated, and storytelling began to predominate. Film and video became more prevalent, and artists employed the narrative structures characteristic of these media. A case in point is the video installation As the Hammer Strikes, created in 1982 by John Massey, in which the artist is seen conversing with a hitchhiker he has picked up on the way to Toronto. The ambient sound from inside the van is heard, along with the two men’s discussions, while, simultaneously with this first projection, two others convey, in alternating montage, the probable thoughts of each protagonists. Massey has trouble understanding the hitchhiker, and the images reveal the contradictions in their communication. The installation inaugurated a narrative mode determined by the fact that artists or their subjects go on journeys that make manifest states of presence or absence—and, consequently, place us in ambiguous spaces. Several artists took to the road in this way, offering (with either critical or humorous aims) unexpected experiences.

Road Runners, presented concurrently at VOX and at the Norman McLaren Gallery of the Cinémathèque québécoise, brings together works and documents from the 1920s to the present day. It will be complemented by a cycle of films entitled Sur les routes, put together especially for the occasion by the Cinémathèque’s curators from March 11 to 19, 2009.