Sven Augustijnen

Spectres

2013.05.11 - 07.13

CATHLEEN CAFFEE

We will institute peace not with guns and bayonets, but with heart and good will. And for all that, dear compatriots, be sure that we can count not only on our enormous strength and immense riches, but also on the assistance of many foreign countries whose collaboration we will welcome so long as it is loyal, and so long as it does not seek to impose a particular politics on us. In this domain, Belgium, which at last has understood the direction of history, has not tried to oppose our independence, and is prepared to give us its help and friendship…1 –Patrice Lumumba, June 30, 1960

Spectres is Sven Augustijnen’s most recent in a series of projects to picture the reverberations of colonialism in present-day Europe. To make the feature-length film, book and installation, Augustijnen spent more than six months accompanying Chevalier Jacques Brassinne de La Buissière, a former colonial government official, as he retraced his decades-old research into the January 17, 1961, assassination of Patrice Lumumba.

Through Brassinne’s own biography, viewers are acquainted with some facts. After seventy years of profit, and often violent colonial rule, Belgium acknowledged the inevitability of Congolese independence by 1960. Brassinne was sent to the Congo to help prepare for King Baudouin’s speech welcoming liberation on June 30, 1960. Afterwards, Brassinne stayed as the Congolese military rebelled against its still largely white Belgian officers. Patrice Lumumba, a hugely charismatic leader of the emergent Nationalist party and the first democratically elected prime minister of the Congo, expelled the remaining Belgian officials from the capital in the weeks after independence. Brassinne then established himself in the copper-rich breakaway state of Katanga, one of the few remaining outposts of Belgian power in the country. There, he worked closely with Harold d’Aspremont Lynden, the Belgian Minister for African Affairs, to safeguard Belgian interests under Moïse Tshombe’s leadership of the secession. Brassinne was in Katanga when, as part of their efforts to shore up the Congo as a Cold War “friend” to the West in Africa, the Belgian military and the American CIA successfully labelled Lumumba a communist, and a strong military leader—Joseph Mobutu—assumed power in a coup. But Lumumba’s popularity remained a threat to this new regime and the Katangan state’s interests. Brassinne would be one of the first to know of Lumumba’s assassination less than six months after Congolese independence.

In the fifty years that followed, Brassinne became a respected, if controversial, historian of the events in which he himself had been an actor, and he spent decades researching who was responsible for Lumumba’s assassination.2 Augustijnen’s film pivots around Brassinne’s conclusion: Belgium did not do right by the Congo throughout much of its history, but in this instance it was innocent. He contends that Tshombe and a number of Belgians acted independently, without orders from officials like d’Aspremont Lynden. To Brassinne, Lumumba was assassinated by the Congolese to silence a powerful enemy.

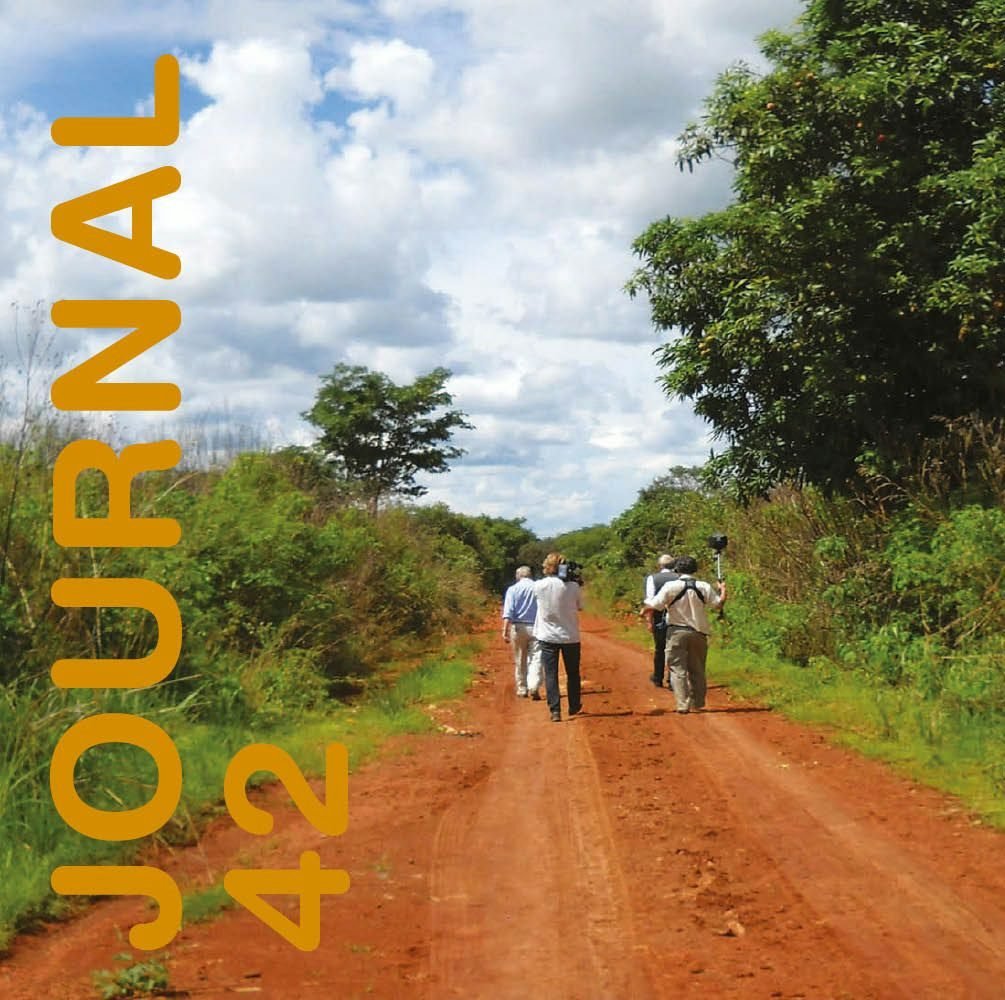

Augustijnen lets Brassinne pantomime his past research and demonstrate how he created his identity as a historian. We see how much he relishes fighting for the facts as he knows them; we watch his graceful discourse with the descendants of d’Aspremont Lynden, and stilted meetings with the family of Lumumba and Tshombe; we follow his dogged efforts to find the tree where Lumumba was shot, and lurid attempts to anchor the killers’ actions in such relics as well as in boxes of dissertation drafts, audio recordings and copies of telexes. Throughout, Brassinne makes sure we see proof that he was there. Such photographs and memories are evidence of his privileged place as a narrator/witness.

In Spectres, Augustijnen uses Brassinne’s re-enactments, as well as long instructional subtitles, obvious camera movement, and theatrical music—Bach’s St. John Passion. This is the repertoire of devices available to the documentary filmmaker. On first viewing of Spectres, these details may seem like the ornamental flourishes of an artist-as-historian who cannot help but put a creative stamp on his material. It becomes clear, however, that the documentary tropes are an integral component of Augustijnen’s ethic in Spectres : a linear, “rigorous” approach to his subject would have contributed to the pretence of transparency that is proper to the documentary form and which is also Brassinne’s own dangerous fiction. Augustijnen knows he is following someone with skin in the game. His own interventions in Spectres—both didactic and melodramatic—underline the film’s fabricated nature and shine a mirror on its narrator’s self-construction.

In the installation alongside his film, Augustijnen bends objects, books, audio recordings and research photographs from Brassinne’s archive into a kind of bridge between the gallery space and his documentary. Brassinne’s images, which picture the widespread violence and murder of 1960–61, are projected as slides, and framed on the walls, while other materials are shown in vitrines. Augustijnen authored a book as an essential complement to the film that is also available for consultation in the gallery.3 It assembles images, biographies of all those referred to in Spectres, reports by a number of historians who disagree with Brassinne, a long interview between Brassinne and Augustijnen, and a detailed chronology from the birth of the Belgian King Leopold II (who established a private colony in the Congo in 1885) to the present day.

Augustijnen treats these supplementary elements with the same auratic reverence as Brassinne did : the archive is evidentiary, and it is also a reliquary. But it means different things to the artist and his narrator. It is through these documents that Brassinne claims transparency—if proof of Belgian guilt is not here, it does not exist. But in the archive, the Congo’s fleeting brush with democracy and its bloody collapse, we see the context in which Lumumba’s was just one death out of millions. All the events of Spectres are the result of one young King’s decision in 1885 that a profitable colony would put his small nation on the map, and another young King’s judgment in 1960 that after seventy years of profit, Belgium could no longer sustain its position as colonizer. The Belgian government did not exit strategically, but theatrically, like an actor departing stage left, and many Belgians waited in the wings. Augustijnen’s devastating exhibition is only nominally inte-rested in unreliable narrators, or in proof of guilt. It doesn’t have to be : the evidence of culpability surrounds us.

1 Speech at the Ceremony of the Proclamation of Congolese Independence, Palais de la nation, Léopoldville (modern-day Kinshasa). (Freely translated)2 Brassinne wrote about his findings in a number of books, including one published under a pseudonym, G. Heinz and H. Donnay, _Lumumba Patrice. Les cinquante derniers jours de sa vie_, (Brussels: C.R.I.S.P., 1966), published in English as _Lumumba: The Last Fifty Days_, trans. Jane Clark Seitz (New York: Grove Press, 1970); see also Jacques Brassinne and Jean Kestergat, _Qui a tué Patrice Lumumba?_ (Paris: Duculot, 1991).

3 Sven Augustijnen, _Spectres_, trans. Emiliano Battista (Brussels: ASA, 2011).