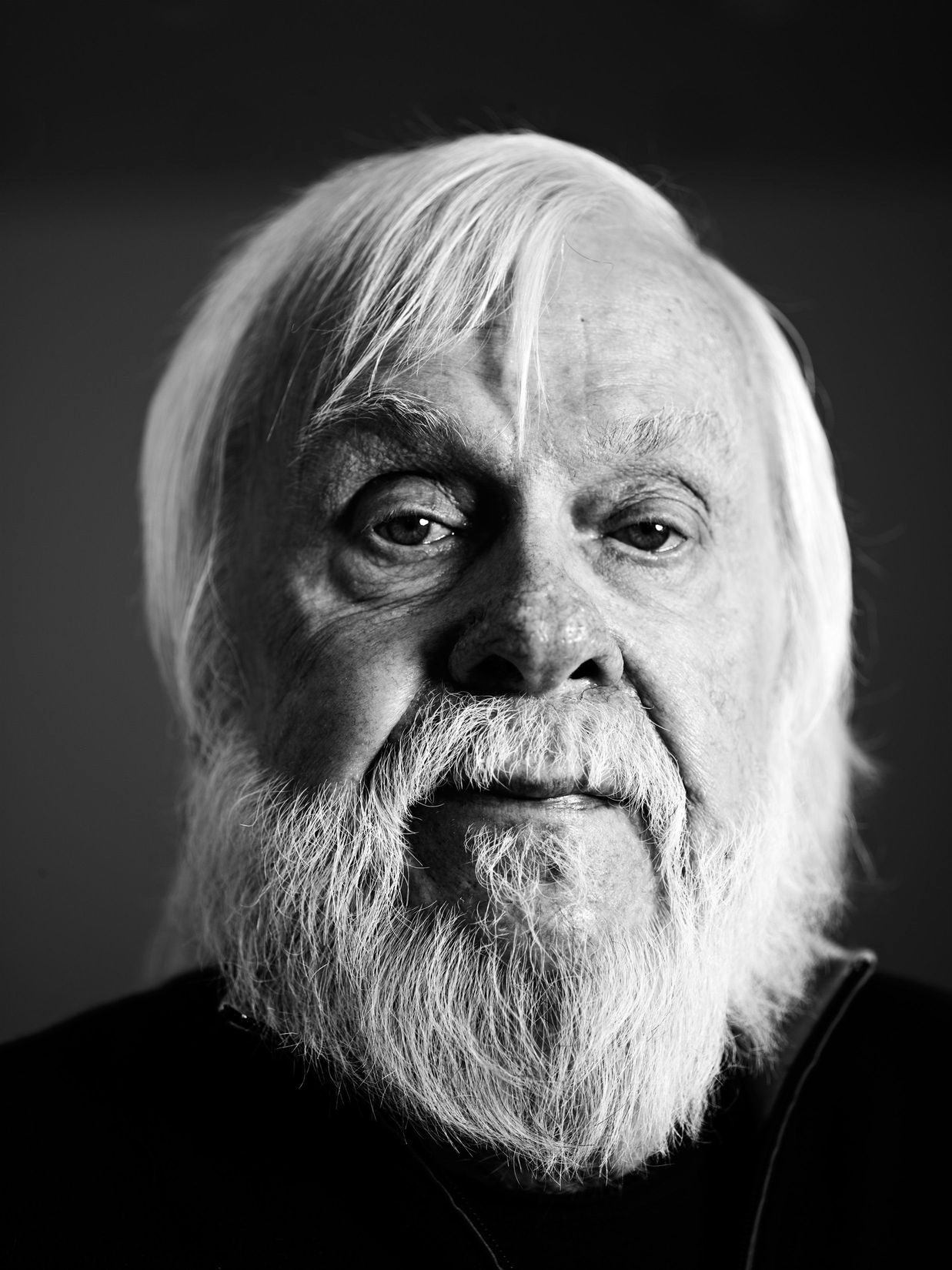

John Baldessari

2010.04.01 - 05.01

MARIE-JOSÉE JEAN

“All art comes from art,” John Baldessari has insisted1. Although the Los Angeles artist has often been viewed as one of the most important representatives of West Coast “appropriationism,” his works—especially his films and videos—are not informed merely by the action of appropriating and recontextualizing existing images or text. Rather, Baldessari treats the appropriated material as a problem. This manner of problematizing art was accompanied by an impertinent attitude that locates his 1970s output within a conceptual tradition, marked by an incisive humour that is absolutely delectable.

The anecdote has become legend: in 1968, Baldessari mounted his first solo exhibition at the Molly Barnes Gallery in Los Angeles. He showed a selection of text paintings that include statements like “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work” (1968). At the same time, Joseph Kosuth’s show opened at the Eugenia Butler Gallery, just steps away. Kosuth was by then, along with Sol LeWitt, an acclaimed exponent of the New York City brand of conceptual art. Having evidently seen the Baldessari exhibition, he wrote, parenthetically, in the second part of his essay “Art after Philosophy”: “(Although the amusing pop paintings of John Baldessari allude to this sort of work by being ‘conceptual’ cartoons of actual conceptual art, they are not really relevant to this discussion.)”2 It is obvious that Baldessari’s practice is not based on strictly analytical conceptual content. The goal is not to produce theoretical art; it has far more to do with ironic thinking, a questioning of the meaning of art and of its system. The irony is integral to the artist’s conceptual approach because it allowed him to mark out a necessary and meaningful displacement between what is read, what is seen and what is understood. And yet, it was precisely that ironic humour that led Kosuth to relegate Baldessari to the Pop artist category. In response to that text, Baldessari made the video Baldessari Sings LeWitt (1972), in which he sings Lewitt’s 35 seminal Statements on Conceptual Art to the tunes of various popular songs, including The Star-Spangled Banner and Heaven. After all, LeWitt had asserted, in Statement 15: “Since no form is intrinsically superior to another, the artist may use any form, from an expression of words (written or spoken) to physical reality, equally.” Baldessari merely pushed LeWitt’s logic a step further in offering a sung version of the manifesto, in the process liberating conceptual art from the unwarranted divide existing between popular and intellectual art. For—as LeWitt reminds us in Statement 33—“It is difficult to bungle a good idea.”3

The exhibition on show at VOX features a selection of conceptual performances and investigations filmed between 1971 and 1977, offering visitors the opportunity to confront John Baldessari’s lucid witticisms.