Chantal Maes

Voyage Out

2010.01.16 - 03.06

CATHERINE MAYEUR

Chantal gives us the impression that she believes her rapport with her craft is improbable, constantly postponed. For her photographs leave us on the threshold—welcoming, yes, but offering no express invitation to enter. She seems to want to say a lot, but in subtle, discreet ways, and she seems hesitant. It’s the same as when she speaks: she blushes, searches for just the right words. But we remain transfixed, tranquil, before such mute intensity, such concentration on saying the unsayable. Before the acute attention she pays to silence or to nascent speech. She leaves us in a thought that is no longer sure of itself. This is healthy. She leaves us nearly speechless; the discursive activity that supposedly is the purview of the observer vanishes. Her work makes us see what really goes on when we are in the presence of a work of art: we are, at first contact, plunged into a reservedness where speech is often absent—a mental magma, a close combat that is turbid, dense and silent. It is not easy to put what concerns us into words, even when the emotion is lasting. Or precisely because the emotion is lasting.

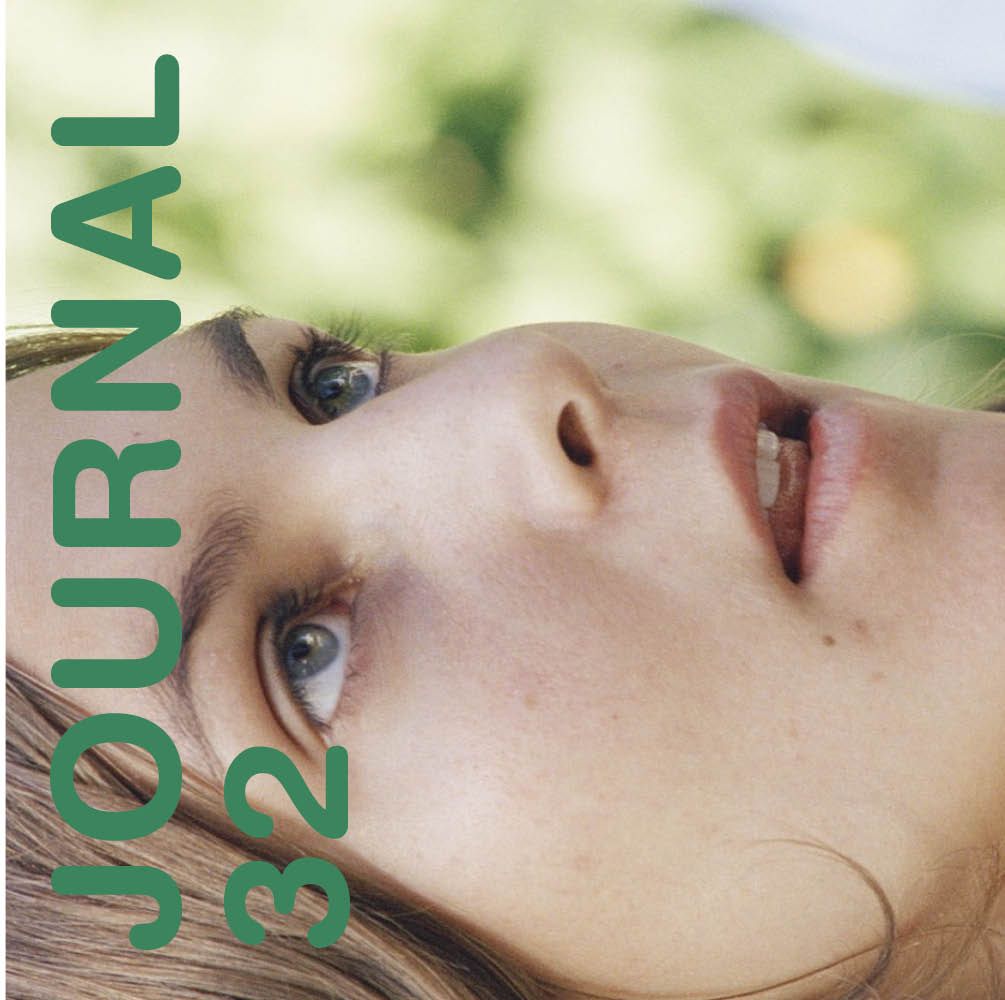

In my recollections, even in repeated confrontations with her photographic portraits—and with her videos that, descriptively, show only words—I always think that Chantal is showing lips. It’s a haunting image. Lips half-opened or half-smiling, lips that are thinking, lips that are hesitating before speaking. That are about to enunciate but are endlessly holding back, seeking the right words. We feel as if won over by the photographers’s gentle, discerning, almost jubilant indecision. The form is perpetually in a state of becoming, even when frozen by the camera. This is a consented choice, which satisfies her, and leaves the spectator hanging.

You have seen her photographs (certainly there is no point in reading a text without having seen the work it aims to describe). You have seen Catherine, questioning herself between two suspended utterances. From one image of this diptych to the other, the mouth traces an almost imperceptible movement, while the eyes remain fixed with the same emotion on the rustlings of the soul. It is as if the subject forgot the photographer as she stared at her lens. A moment of grace, they say. Nothing but evanescent, yet complicit, speech. In the case of Laurence, the duration of the thought is spoken in the inconceivable temporal contraction of the single photograph.

With Inward Whispers, begun in the late 1990s, Chantal had already condensed an indeterminate period of time, a hiatus within life, in each image. This series of portraits of airport employees laid bare those moments that we describe as “absent-mindedness” when they in fact afford us an inward perspective, even if it is made up of driftings—of shifts that elude awareness. The widened eyes seem to open up onto a space of sheer inwardness. Their bewitching silence nonetheless hints at an interior monologue, full of breaches and branching-offs, of uncontrolled articulations.

Voyage Out was in a sense an extension of the previous series, since, by her own admission, Chantal strove to “make visible a mental wandering”—a reference to Nathalie Sarraute’s Tropismes. The faces in close-up suggest a subtle oscillation between self-presence and porosity to micro-events occurring outside. The models’ wandering, between concentration and availability for the most unexpected associations, conveys that of the photographer at work, and unmistakably refers to the viewer’s thought processes.

With the video installation Take a Look from the Inside (a title that would be an apt descriptor for all of her work), Chantal follows ever so closely the mental workings generated by the act of reading. Very clearly, she makes them visible through the movement of the camera, recording a printed page, a segment at a time, while speaking the words aloud in a dislocated cadence—that of decryption through the viewfinder. The staccato scrolling of image and speech creates a dizzying mise en abîme of Christian Dotremont’s text Qu’il nous arrive de bafouiller. We are thrust into the very heart of creation in the process of being said, in contrast to the opaque plane of the blank white page.

Which brings us back to photography, to the screens/faces, which paradoxically afford glimpses into the unplumbable depths of being, and to the recent landscapes. The centrepoint of these views of urban space is a pair of images that, according to the artist, mark a return to awareness, a surging forth of the present tense. A child dressed as Spider-Man runs through a park; a white, blurred van seems to float in a street. They are headed toward us, indeed revealing an incursion from the outside—but, to my mind, these enigmatic loomings still engender a feeling of absence. The arrested movement of the masked boy and the spectral, derealized appearance of the vehicle manifest themselves in a similarly suspended space and time. And indeed Chantal had to return to the scene with her view camera, reducing the playground to a space of singular emptiness. The landscapes, though still linked to the city, seem dehumanized, establishing themselves as deserted scenes, where even the sky is absent, and one comes up against these highly constructed two-dimensional expanses. The all-over depiction of the trimmed hedge proves emblematic, its opaque surface intensifying the flatness of the photograph. These views—which in fact are no more “landscapes” than the faces are “portraits”—also evoke trains of thought, here exteriorized by a spatial shift (the modified perspective, the blurriness) or a temporal one (marked, for example, by the change in climate). Repetition functions like a spreading-out of thought. The coherence of the work asserts itself, beyond all thematic concerns.

A few days ago, Chantal mentioned to me a certain affinity with the work of Walker Evans. Though I hadn’t made the association before, I can well understand it now. She initially referred, not surprisingly, to the New York City subway studies, Many Are Called, with their testimonials to errant thoughts in that transitional space-time, where close quarters demand a retreat into oneself. But what unites these two vastly different auteurs, more generally, may well be a belief in the aporia of the photographic portrait. That, and the assertion that the image cannot extend beyond the surface of the visible. Even more so, their works remind us of the vanity inherent in the desire to say or show everything—and in the conviction that pictures reveal some kind of truth.