Jeanne Dunning

2007.11.03 - 12.15

RACHEL LAUZON

By evoking the artificial—flesh-coloured nylons, a false outgrowth, a gelatinous skin-coloured mass—Jeanne Dunning maps out a reflection on the relationship to the female body that, instead of questioning the domain of appearances, is rooted in the deconstruction of the relationship to the flesh. The artist examines the connections between the flesh and the Self, looking beyond questions of seduction and power.

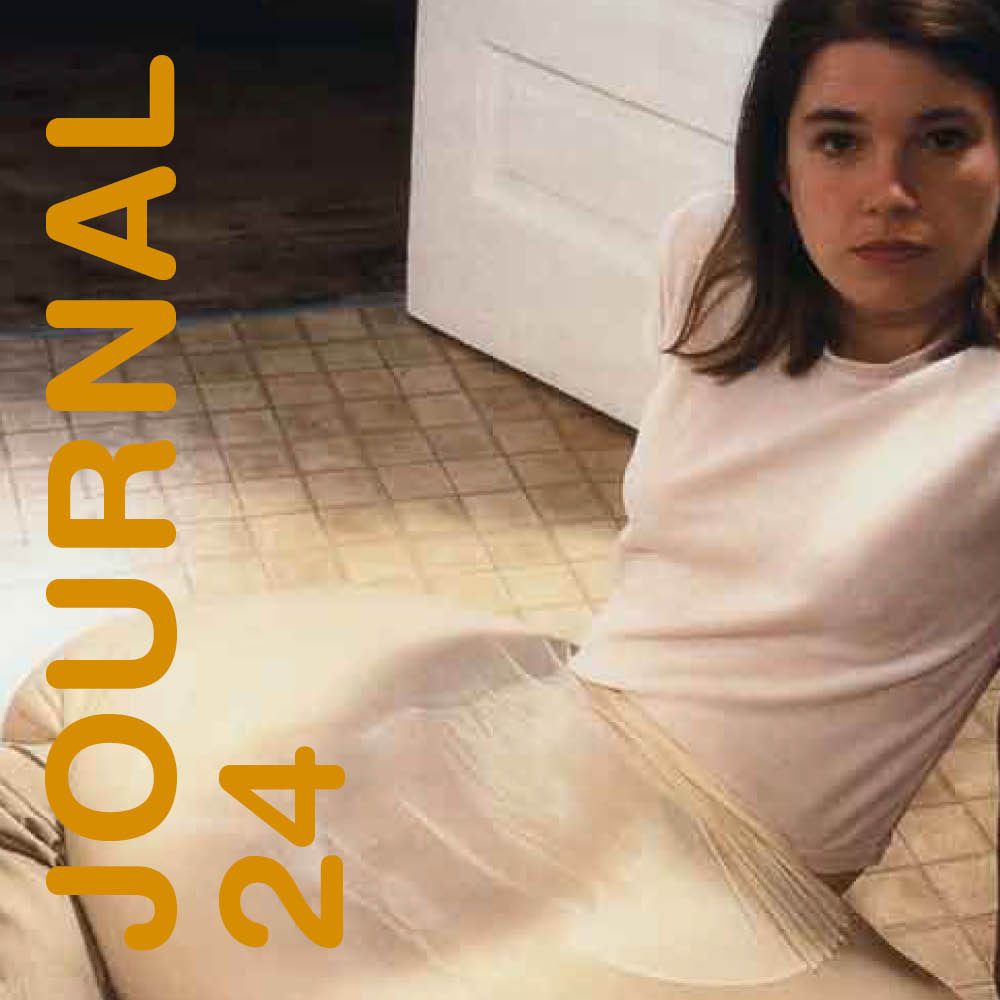

Fragmented bodies (Scattered Parts), inert flesh (Getting Dressed), excess flesh (On a Platter): Dunning’s thematic reinforces the ambiguous and destabilizing scope of her images, and speaks, more specifically, to a certain detachment vis-à-vis the flesh. The artist not only considers the excess flesh as a whole unto itself, she also seems concerned by the paradoxical relations maintained toward the body. Her works are a consideration of the body as being constantly torn between the protective dimension of its flesh and the suffocating nature of its mass. The series The Blob is an eloquent example of this ambivalent relationship. Some of the images present the aqueous mass as burdensome; at other times the same shape seems to be a reassuring presence. Thus, the blob can just as easily evoke the soothing warmth of a body, as it can the clear absence of a true body embodied alongside the subject. As a result, the ambiguity between desire and solitude, solace and emptiness, fantasy and the inability to act problematize the relationship between the Self and the Self’s extension into the corporeal envelope.

This difficulty in establishing a contiguous relationship between the body and the world in which that body exists is evident in the works Extra Skin (Adding) and Extra Skin (Subtracting). In the former, a character pulls on various layers of flesh-coloured clothing, thus alluding to a thickening of the flesh despite the artificial dimension of the beige-y colours—as if this new fleshly coating, almost prosthetic, now has a more protective, rather than sensory, function. In the latter work, a woman delicately (and falsely) peels off the surface of her skin, and lets it pile up on the ground. These images provoke questions that have to do with the Self: is naked contact with the Other (im)possible? How can one really penetrate one’s own mortal coil in order to come into contact with one’s Self? And just where is that Self, after all? Inside the body, or in our relationship to the Other?1.

The work Trying to See Myself seems to sketch out something of a response to those questions, again related to the idea of detachment. When the woman removes all at once the multiple layers of tights that she has brazenly slipped on, when she succeeds in disengaging herself from that envelope of false flesh, when she delicately replaces that synthetic matrix, it appears that she is at last capable of “seeing herself”—as if detaching herself from the cast of her body lying on the ground, like an empty cocoon, were the only way of affirming the reality of her fleshly existence in the world.