Loretta Fahrenholz

2018.04.19 - 06.30

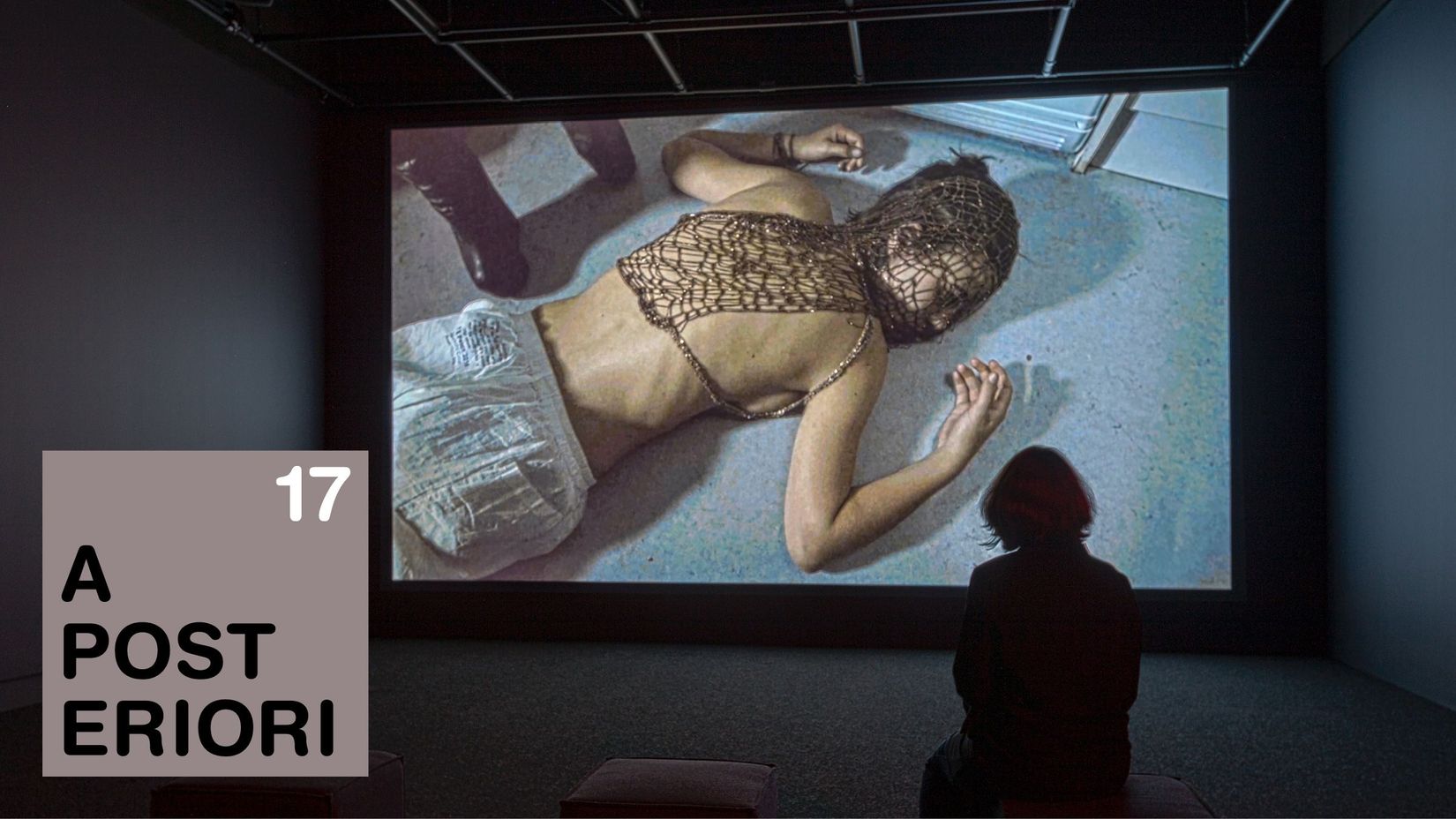

German artist and filmmaker Loretta Fahrenholz examines fictions and desires that take shape within different communities: a street dance troupe performing in a city in the midst of crisis, a blended family, young men in the age of cybercapitalism, a clan with telepathic abilities. The artist employs tropes from specific genres—disaster, fantasy, documentary and porn films—to elicit narrative and formal contradictions that, in turn, facilitate or hinder their identification. While at first glance the films appear to be structured around indirectly linked events, a throughline is eventually discernible, fascinating the viewer.

Her works are often inspired by literature (After Midnight, Irmgard Keun, 1937; Implosion, Kathy Acker, 1983) or cinema (actor Ulli Lommel, directors Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Shirley Clarke and Frederick Wiseman), but this cultural referencing is never limited to citation. Rather, Fahrenholz chooses to restage the original works’ syntaxes and locate their narratives in contemporary settings, causing new meanings, imbued with strangeness, to emerge.

Reflex Effects —Surveillance and the Reflective Subject in the Films of Loretta Fahrenholz

CAROLINE BUSTA

93% of all crimes are crimes of vanity.

—Irmgard Keun

Danton speaks: “Your eyes work the same way mine do, you cunt.” The revolutionary Danton, charged with corruption, has been sentenced to death by Robespierre without trial or the possibility of offering words of self-defense. Or at least such is the case in Implosion—both Loretta Fahrenholz’s 2011 film and its tongue-in-cheek referent, the 1983 Kathy Acker script, which stages the French Revolution in the bohemia of a newly post-Fordist NYC. In an earlier scene, Danton’s fate is foreshadowed by the character My Grandmother, who, asking his whereabouts, interrupts herself, almost as if to answer her own question: “Fiction. I tell you truly, right now fiction’s the method of revolution.”

In Fahrenholz’s frame, Danton and Robespierre volley lines of subjectification. Danton’s words are a response to being asked what he sees: “Your eyes work the same way mine do, you cunt.” As if to say (to Robespierre, to the others), I see you. I see you seeing me. I see you seeing me as embodying your fiction x or fiction y or fiction z. And so I almost cannot help but perform the fiction you believe me to be; and anyway the stage is already set and I am typecast within it, and so even if I present a corrective of myself minus x, I am still staging a fiction, playing into or against your subjectivity, your vanity, and who I take you to be.

It would be obvious here to speak of Brecht, who of course took as paramount the actor who “makes it clear that he knows he is being looked at” and meanwhile also “looks at himself.”1 One could say all too simply, perhaps, that Fahrenholz encourages her characters to fold in the fourth wall, so that their experiences of not just the camera/viewer but also of each other create disjuncture, moments of the “real” that interrupt the process of consumption or recuperation. But such themes of Marxist alienation now feel hackneyed and somehow anachronistic; one might even say that given Fahrenholz’s generational and cultural context (that of a German steeped in a history of Brechtian theater who is now frequently based in New York, where Brechtian devices are more than occasionally deployed, especially in younger art-academic contexts, as a kind of critical trope), such direction even reads as a kind of camp. Taking a different angle, one could also read such setups as the poststructuralists might, speaking of identities not as a burden to escape but rather as an interface to be “collectively formed.”2 In Fahrenholz’s film, Danton and Robespierre are, like every individual—revolutionary or not, proletarian or elite, public figure or relative unknown—at his or her core, a collective fiction. The processes of individuation, of subjectification, the experiences that compel one to perform as x or y or z, however, are very real.

If this logic holds, it might offer some other insight into to Fahrenholz’s working process, and thereby a key element linking the seven films represented in this book. Regardless of who Fahrenholz has cast—be they professional actors, children, close friends, or individuals found online—the directorial focus is centered on establishing and manipulating the mechanisms of subjectification much more than on the management of the particular subjects these mechanisms produce.

In the case of Implosion, for example, Fahrenholz quotes a certain video art convention, one derived from a particularly art world fantasy of transgression—i.e., the so-called underground of Acker’s downtown 1980s New York, which itself is in part self-consciously modeled on the bohemia of Dadaists and other earlier avantgardists (Gertrude Stein, William S. Burroughs, etc.) and has in recent decades radiated out, replicating itself as a value indicator of artistic “legitimacy” via such outlets as American Fine Arts and Reena Spaulings Fine Art in the ’90s and ’00s, and now also perhaps the transnational poetry-based scenes that, communicating via group chats and mssgr feeds and other cyber-channels, physically cohere intermittently in Berlin/London/NYC/LA. Fahrenholz has tapped this persistent strain of “radical chic”—one as undying as porn—layering Implosion with various conventions of both: revolutionary spoken word, kinky techno music, gender ambiguity, Adonis-like bodies, the street versus a chic but haphazardly appointed financial district apartment, ostensibly squatted by this cast of millennial creatives. More than just sexual explicitness (although there is an element of this too; enacted, no less, with near-farcical dispassion), Fahrenholz establishes a general feeling of obscenity—one that comes with the making-immediate, by way of money or other currency, of that which is both inaccessible and highly desired. What Implosion offers up is the revolution’s collapse—the death of one radical at the hands of another—played out by young bodies flowing and freezing Merce Cunningham– style within the vertiginous confines of a small but dramatically windowed Manhattan high-rise.

In good Brechtian fashion, there is here an understanding that not only the actors, but also the film’s viewers possess subjectivizing authority. Danton, again: “I only believe in what I can see.” Though Acker’s script specifies some twenty characters of various classes and ages and genders, a cast of just five (with each playing multiple roles) populates the video. But, to draw on French thought again, Fahrenholz, meanwhile, steps aside to allow these vectors to act on the subjects, the narrative, and the various “messages” sent out and intercepted. With this film, assumptions are short-circuited before particular ideations of individual bodies ever have a chance to sediment as fact. Fiction, in this light, is not something to be avoided or deconstructed, but rather to be generated for its revolutionary potential.

Take as example her 2013 film, Ditch Plains, which is set in the apocalyptic landscape of post–Hurricane Sandy NYC. Loosely narrative, it plays out like a sci-fi version of Grand Theft Auto, sited, choreographed, and staged in close discussion with several members of the all-black, East New York–based dance crew the Ringmasters. Among the scenes this film includes a stop-and-frisk exchange3; a raid, by the dance-crew-members-turned-zombies, of a posh Park Avenue flat; the zombies, illuminated with special LED-trimmed clothing, pretending to pick off enemies with a mimed .50 caliber sniper rifle from the porch of a fire-ravaged house (the result of a homophobic hate crime) in the Ringmasters’ neighborhood. This text need not spell out to the reader how such vignettes, particularly during a time of mounting racially motivated violence (which would soon cohere in the Black Lives Matter movement), might register to a left-leaning American viewer. Were Fahrenholz’s detractors wrong, in the wake of the film’s release, to position her as a voyeur in this equation, calling out her ostensible desire to see certain subjects playing out these scenarios? For those who know the circumstances of the film’s making, yes, this claim is false—even speaking to some fantasy, on the part of the critic, of the filmmaker as exploitative director. If anything, Fahrenholz, aware of the potentially charged readings this work could elicit—a consideration with all of her films—worked in ways that allowed the actors to negotiate their own representation in the process of shooting. Questions of where a gaze originates, where it falls, and whose POV determines the work’s dominant lines of subjectification necessarily arise. But Fahrenholz aims to effect this ambiguity, playing with degrees of fact and fiction to the point of triggering such reactions.

2.

It’s a set of questions asked across social media as users parse their feeds some billion times a day: Whose truth/fiction is being offered up? Who has authored it? Endorsed it? Who benefits? Who does it blame/exclude? And, in a nanosecond, then: what is my spin? After all, given my upbringing/race/relationship to gender/particular trauma/event witnessed/academic level achieved, I must speak up; people will want me to speak up; I will be heard if I speak up. Factored into this: the optimal leveraging of one’s network and positioning of oneself within it. “93% of all crimes are crimes of vanity,” writes Irmgard Keun, whose 1937 novel After Midnight—penned amid the hysteria of pre-war Nazi Germany—stands as inspiration for Fahrenholz’s latest film, Two A.M., which she shot and edited this summer as the seeming implosion of multiple systems of global governance transpired around her.4 This is to say that if the 1930s can be characterized as a period of relative instability, the present moment—what with, in the past month alone, numerous globallyvisible acts of terror, Donald Trump’s US presidential nomination, Brexit, and the Turkish military’s foiled anti-Erdogan coup—shares the stimmung of precarity that described Keun’s time too.

Though it would cause her to go into exile (and even to stage her own death), Keun’s writing is remarkable not least for its subversion of the power structures that came to shape her world. In her novels, Keun takes up the conditions of her day, deconstructing the agency of the era’s main protagonists by deploying her story from the perspective of regular people finding their way through the contradictions of that political moment. Fahrenholz’s time, however, presents from the outset, not a linear history of victors, but a spectral history of versions5—one wherein each macro-community lays claim to a story (or better said, collective fiction) that gets more or less equally advanced (despite attempts at remediating the words of the chancellor, the president, the paper of record) as there is no longer any unimpeachable meta-authority capable of verifying one narrative as more or less valid than the next. Rather, each community presents its history by recounting its events across a cast of particular bodies, each assigned different roles: victim, hero, “other,” one of us. As with Fahrenholz’s direction of Acker’s script, certain bodies thereby find themselves playing various and possibly conflicting characters depending on the scene—which does sound very Brechtian. The effect however, as it’s playing out on the real world stage at present, is proving to be anything but distancing. Collective fictions can indeed also be horrifically negative, cohering into violent, decidedly dystopian tribe-like convictions.

Such topological dynamics mean that an “other” is defined explicitly so that a self can be articulated in opposition. A recent tweet: “Everyone’s a cop. Everyone polices to enforce [give credence to] their beliefs.”6 Whatever one sees in the other, whatever information can be collected therein, can be used as raw material for forming oneself in contrast. Of course, this truism has an inverse: there is also a deep human desire to be someone else’s raw materials, to be seen as someone else’s fantasy (cue: lonely girl), to harbor the idea that one’s own image and content might be significant enough to influence another person or even contribute to the shape of an entire collective, community, movement, brand. Certainly social networking has shown these modes—that of the viewer/consumer and the exhibitionist/contentproducer— to be two sides of the same coin. Friendster is “a rudimentary version of what would become the Internet’s answer to crack cocaine,” read an article in the November 2003 issue of Spin magazine, identifying from the outset the sincere desire—even as America’s Patriot Act, contemporaneous with the rise of Web 2.0, legalized the government’s carte blanche surveillance of its citizens’ online activity— to project an identity and to, in turn, be the basis of someone else’s fantasy.7 Or at least that is one compelling answer to why a Generation X, though socialized by the ethos of underground Acker-like codes and ’90s indie and rave cultures, began all at once and en masse voluntarily profiling themselves, subjectifying themselves, building out digital nodes like catheters for transporting the affective, identificatory information that just a few years prior they would have protected, at all costs, from corporate and government view.

In Fahrenholz’s Two A.M., the cast is split: on the one hand, there are the Humans—an affable, generally urban-dwelling caste, they spend their free time in bars and shopping malls or making handcrafted jewelry out of upcycled trash. The Watchers are the other group. Loosely based on the NSDAP members that populate Keun’s After Midnight, they are informational voyeurs, possessing a keen interest in everyday citizens; they live rurally, and are seemingly old fashioned; also, they claim to protect the Humans. But their super power—the ability to read minds—allows them, meanwhile, to take dubious pleasure in scanning brains, collecting as much information as possible. There is little the Humans can do to avoid the Watchers’ gaze. And so the Humans live with this relationship, accepting this strange intimacy. Perhaps they’re even slightly jealous of the Watchers, as they, too, desire to know each other’s thoughts. But the Humans know that the Watchers scroll through minds, scanning fears and desires the way we scroll through newsfeeds—a coup, a cat, a meteor, a mass murder. And indeed the Watchers, like the NSA, “intercept almost everything, ingesting human communications automatically without targeting.”8 Ingestion, that’s key. In both cases, individual subjects are consumed; taken in as part of a stream of life events and affective modes that might catalyze micro-bursts of dopamine. In the film, some of the Humans are aware of their narcotic effect on the Watchers—or at least Sanna, the film’s leading character, is. In turn, she understands that the Humans do in fact have a kind of control over the agents of their surveillance, that the power vector operates both ways.

Collective subjectivities, co-dependent desires: “How can desire desire its own repression, how can it desire its own enslavement?”, ask Deleuze and Guattari, answering that “the powers that crush desire, or subjugate it are already part of the arrangements of desire themselves.”9 In Fahrenholz’s films, vectors of desire and constructions of control are constantly shifting. In part this is due to the character descriptions, which never make clear which roles have authority over others, leaving it to the actors and to the viewers to, through body language and gestures, send and receive cues as to who is in control. There are also cinematic devices that modulate the viewer’s perception, not least the switching between handheld video and steadycam shots, bringing the viewer into the space of the action and then placing her outside it in a God-view surveillance zone.

Many of the aforementioned early adopters of Web 2.0 abandoned their avatars by the end of the ’00s, “killing” their Facebook profiles and even rejoicing in the deaths of their 1.0 smartphones. But even as a non-participant of social media, today one is still essentially obliged to regularly ping the network at large (a neo–fourth wall of sorts), making oneself visible to it, vulnerable to it—but also, one would hope, in good avant-gardist fashion, messing with it, trying to break it or mislead it, to overload it with information and versions of selves that never quite match up with their respective bodies. To return to Acker, albeit shifting the intended meaning of her words: “Fiction. I tell you truly, right now fiction’s the method of revolution.”

This exhibition is presented with the kind collaboration of Galerie Buchholz. VOX is grateful to the author, Caroline Busta, as well as the Fridericianum, Kassel, Kunsthalle Zürich, and Koenig Books, London, for granting permission to reproduce this essay published in Seven Films by Loretta Fahrenholz, 2016.