Mathieu Cardin

What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain

2020.01.11 - 03.07

Museologists have traditionally defined the exhibition as a visibility apparatus enabling us to deduce knowledge about culture, nature, art, and so forth. In a new installation devised specifically for VOX, Mathieu Cardin imagines stagings that “exhibit” the visibility mechanisms we might normally find in a natural history museum.

His reliance on a route composed of stations, reconstituted scenes, illusionist effects, informational panels, artificial artefacts and settings, however, delivers a most peculiar experience of nature. The key, no doubt, is provided in the title of the exhibition itself, borrowed from a well-known 1959 neuroscience paper that explained how a frog’s eye not only conveys to the brain different levels of brightness, but a set of visual stimuli enabling it to perceive light according to a previously structured and interpreted language.

In describing the mechanisms operating within this staging of nature, and then reframing them in images, Cardin seeks not to “show” or even “demonstrate” any thing; rather, his aim is to “exhibit” the relations between things, and those between nature, its perception and its representation, which is often problematic.

BÉNÉDICTE RAMADE

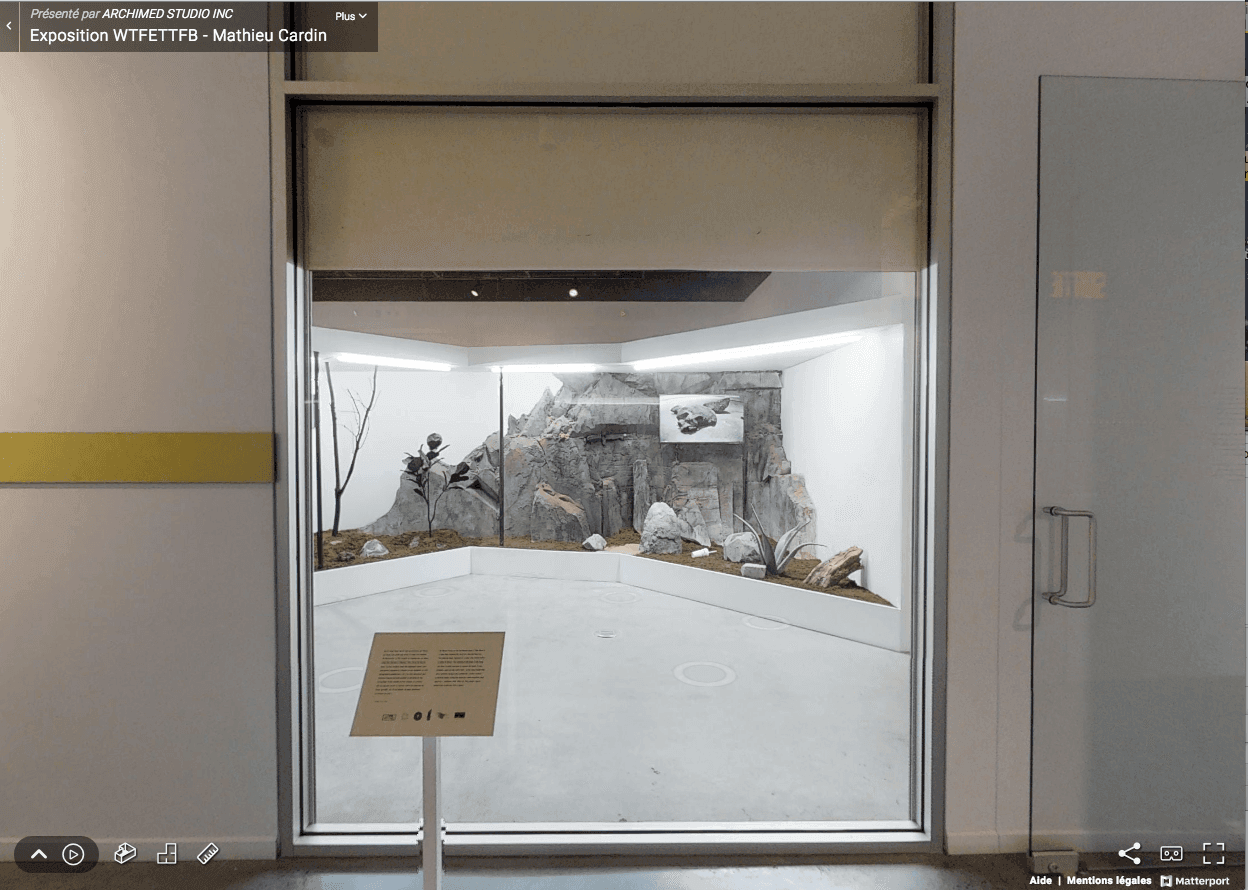

The glass wall of the vestibule through which a portion of Mathieu Cardin’s exhibition appears issues a de facto call to exercise curiosity, to come closer while remaining shielded, to initiate an inquisitive gaze ready to scrutinize the “tableau” that every vitrine creates. The presence of an accompanying informational sign is a further stimulus for our brains to shift into “inquiry” or “event” mode. There is definitely “some thing,” perhaps something alive, in this diorama scene. With its harsh lighting, this peculiar terrarium, furnished with sombre vegetation, certainly has something “live” about it, but nothing alive: it is happening as part of a live transmission, on a screen, right there across from the glass wall behind which we are standing. But the point, precisely, is that the moment has passed into oblivion: a skull lies on the ground, surrounded by stones resembling those visible in that first environment exhibited right here, in front of us. The trap gently closes; incomprehension reigns. And it will intensify as our visit to this Museum of Not-Quite-Natural History continues, with its reconstitutions, meticulously produced as in the finest dioramas, hiding many tricks.

Like his precursors Dan Graham and Bruce Nauman (Video Surveillance Piece : Public Room, Private Room, 1969–70)—who are past masters of the art of the out-of-phase, of surveillance video, of depictions of the act of looking and watching—Cardin sculpts the video signal, including feedback. He knows that we are drawn to screens, that our eyes will first scan surfaces before considering spaces. The screens of the glass wall at the entrance, then those of the video monitors, cleverly programmed to exploit spatial telescopings—these are the media through which we begin our visit of each “tableau”: a skull, a misty mountain range, the eye of an amphibian. Each of the three images is seen in a transmitted environment before being physically experienced. Cardin’s exhibition draws us through his universe, station to station, from these manufactured naturalist settings to a concealed room at the end of the route, which uses trompe-l’œil effects.

At this point our relationship to the filmed reality turns strange. What timespan are we watching? Is it a prerecorded loop? Some surveillance record of spaces that we can’t double-check with our own eyes? These disconnects between image and context intensify as we move backward through an initial scene that is hyperrealistic and yet slightly off-kilter: there’s too much black in these entirely manufactured everyday plants. Nothing here has ever been alive; it’s all been “fixed in post-production”—in more ways than one. Everything is too static for any type of life to have ever existed here.

After combing through the terrarium seeking keys to understanding, our gaze lands on some fog-shrouded mountains that are not unlike the Romantic landscapes that Mariele Neudecker imprisons in her “tank works,” boxing the sublime beauty of highlands enveloped in “vapours” made from chemical precipitates. There is nothing natural about Cardin’s cloud formations either, yet they seem awfully “real”. Here again there is a disconnect between the image generated and the installation that reveals itself once we are past the wall on which the monitor hangs. More space-time confusion results from a corridor in which we encounter a long glass box, another monitor, this one showing a bizarrely immobile eye, images, and the sacrificial circle from a prehistoric age whence emerges the infamous skull, as if burnt. The spear that pierced it sits in an acrylic reliquary, which the display arrangement presents as more precious than the cranium it had shattered. We must negotiate another corridor to discover a half-open sliding door, behind which is a lounge, violently lit and austere. The disconnect here is between the timeframe of the exterior prehistoric scene we have just observed and that of this room, dominated by a surveillance monitor—a metapiece in the exhibition, because each view in the surveillance mosaic is transmitting each of the tableaux we have visited since entering. Even the surveillance room itself is being surveilled. All this time, our actions have been seen, captured, monitored. But by whom? Apparently by the agents of some corporate entity who are absent, even if its logo is everywhere. An all-seeing eye, it has been scattered in the exhibition space shortly before our arrival here: on badges, a table, a mug. Paranoid in the face of this idle surveillance, the visitor entering the room finds their own gaze shifting from contemplation to mistrust and suspicion. “The apparatus thus has a dominant strategic function. . . .” as Michel Foucault wrote. “The apparatus is thus always inscribed in a play of power, but it is also always linked to certain coordinates of knowledge which issue from it but, to an equal degree, condition it. This is what the apparatus consists in: strategies of relations of forces supporting, and supported by, types of knowledge.”1

In September 1959, MIT researchers Lettvin, Maturana, McCulloch and Pitts published their study of the frog’s optic nerve, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” describing a cognitive structure far more complex than what science had surmised up to then: the amphibian does not merely respond to light stimuli according to a basic-reaction principle, but can combine movements and thus perform a much more refined “reading.” The paper, which proved foundational for artificial intelligence (AI) researchers, demonstrated the capacity of a frog’s optic nerve to encode information, and from that point was useful to development of reference models. Reading that paper provided Cardin with the blueprint for his exhibition, its title, and an entire construct of retinal stimulations that titillate the eye and brain of the visitor-cum-guinea pig.

In his 1984 essay “The Consequences of Causal Thinking,”2 Rupert Riedl describes the skull of a Neanderthal man impaled on a spear, inside a sacrificial circle of stones—the same scene that is continuously monitored as part of the exhibition, the image of which, filmed in real time, impels the journey through another time, frozen in reproduction. From the pieces of the puzzle we begin to infer how the artist has apprehended the space entrusted to him, constructed environments that interlock to create a compact place, managed down to the millimetre as befits the art of mimetic reproduction, while eschewing the mere linear timespan of the visit via screens and spatial skippings. Normally, facing a diorama, our gaze is stable, guided, instructed with full confidence; here, it is systematically frustrated, pushed farther away, removed from the didactics of the staging of a milieu, of a situation frozen in a museum-going instant.

Mathieu Cardin’s situations are created to spark doubt, to prompt us to analyze our visual capability under such conditions. As we examine two photographs, one of which shows a fly and the other the hind legs of a frog, the complexity of processes becomes a metaphor for the entire trap we have fallen into. In each of these images created by the artist (a scan of a plastic frog and a photograph of a real insect) the resolution has been downgraded and the resulting image fed to an AI software application designed to enhance low-definition images. That enhancement comes at the cost of extra pixels “invented” by the app. After multiple iterations in which Cardin has downgraded the quality of the image artificially “upgraded” by the app and repeated the process, the original photograph has ended up distressed—with, among other things, liquid “shake” artifacts that accrue from one “printing” to another. Thus the photographic medium, which has always been a temporal sensor, here layers so many processes and refinements that they disable the readability of the subject. Too many temporal strata, too many “de-finishings” and too many definitions: never has the term “artificial intelligence” been such a misnomer.

3D Exhibition Capture