Naeem Mohaiemen

2016.05.11 - 06.25

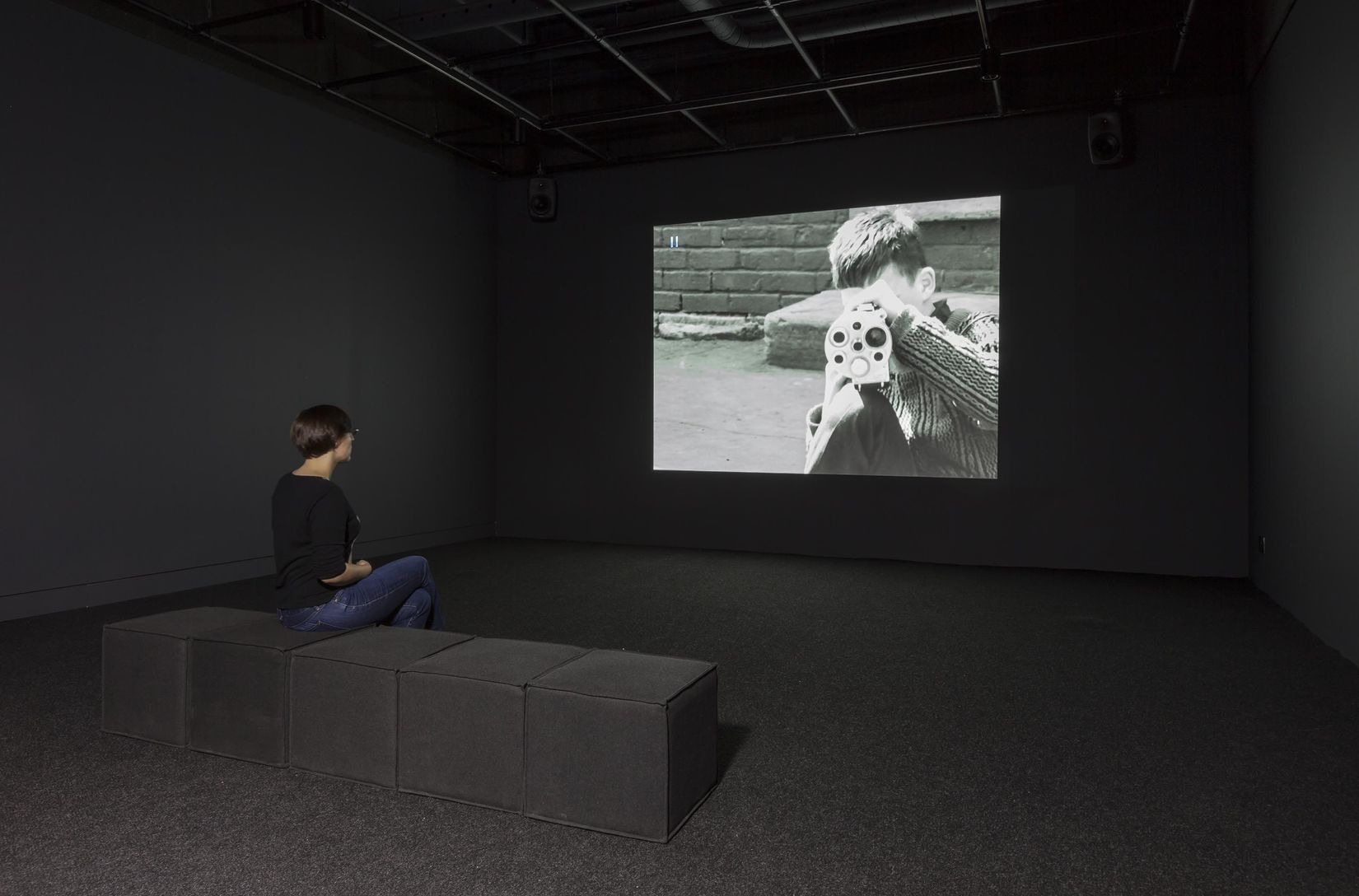

The Young Man Was

What lies behind utopian hope, especially within the idea of socialism, against the weight of history and experience? What also of the men who survived those terrible times, unlike so many of their comrades, and now spend their waning days in solitary apartments, writing down memories? What was such a man then, and how does he remember himself today? Was he John Reed, recording the Russian Revolution, in the last free moment before the Thermidor? What does it mean to be a survivor and witness—the last man standing on the eve of another collapse, surveying the wreckage of the socialist dream in the middle of a horrific present that teeters on the cusp of the Anthropocene?

In his practice as a historian of postcolonial reimagining, Naeem Mohaiemen uses text, photography, and films to explore failed utopias within the historical narratives of the international left. His research looks at borders, wars, and belonging within and outside postcolonial nation projects. Since 2006, he has been directing a film series entitled The Young Man Was, in which he examines the failures of radical leftist movements of the 1970s. The series was produced using sequences from existing films, archival footage, television reports, interviews, and audio recordings. The first part (United Red Army, 2011) examines the 1977 hijacking of Japan Airlines Flight 472 by the Japanese Red Army; the second (Afsan’s Long Day, 2014) addresses the circulation of ideologies from the perspective of a young historian (Afsan Chowdhury, whose diary entry gives the series its name) following the events of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, juxtaposed with those of the German Autumn associated with the Rote Armee Fraktion (1977); and part three (Last Man in Dhaka Central, 2015) traces the journey of Peter Custers, a Dutch journalist who was jailed in Bangladesh in 1975, accused of belonging to an underground socialist group.

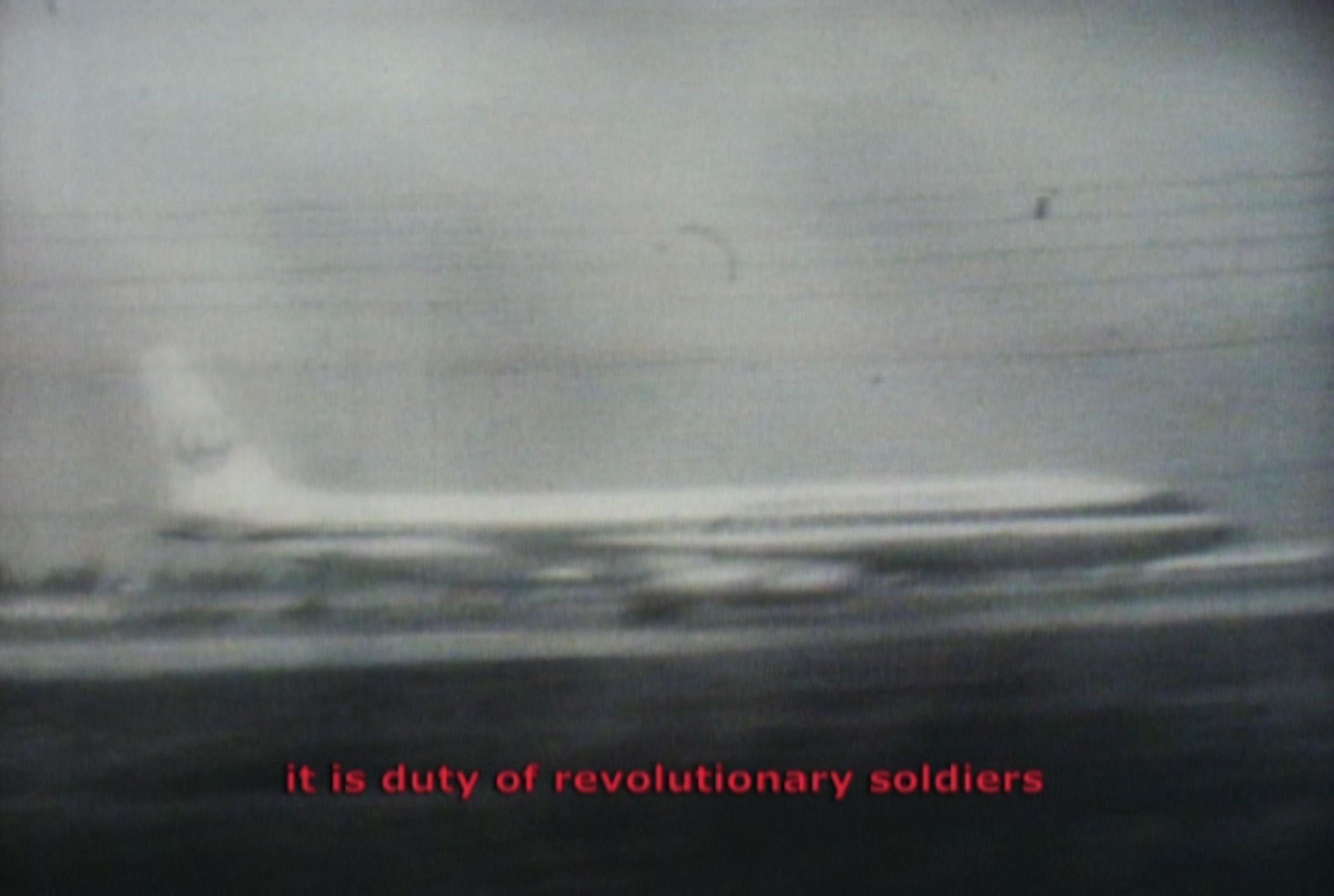

United Red Army (The Young Man Was Part I), 2011, 70 min

September 1977. The Japanese man speaks in halting English; the Bangladeshi negotiator, with the clipped confidence of an army officer. A colour scheme suggests order in the exchange: green, red, and the occasional white. But underneath the schema of a dark screen—subtitle sans image—lies a waiting unravelling. The Japanese Red Army had attached to the Palestinian cause, and through that to an idea of global pan-Arabism. But the high-value hostage turned out to be an Armenian banker from California, and the Democratic Party Congressman on honeymoon negotiated a call to the White House, only to be greeted by Jimmy Carter’s answering service. The hostage terrain was not an “Islamic Republic,” as the hijackers thought, but a turbulent new country ricocheting between polarities and imploding in the process. Two years earlier, the country had gone through a trio of military coups, decimating, in turn, the country’s founder and Prime Minister Mijubur Rahman, his family, a group of freedom-fighter army officers, and finally, a Leftist insurgency group within the army.

Instead of being the willing platform for the Japanese Red Army’s ideas of “Third World revolution,” the actual Third World hit back in unexpected ways, turning the hijackers into helpless witnesses. The lead negotiator, codename “Dankesu,” says with baffled understatement and halting English: “I understand you have some internal problems.” An eight-year-old watches the television screen with growing confusion—the screen shows an unmoving control tower for hours on end, and he wants his favourite show to start again.

United Red Army premiered at the Sharjah Biennial in 2011. Sarinah Masukor described the film’s structure, specifically the archival images, as “ever on the verge of collapsing into abstraction, their materiality performs the indeterminacy of the event they record” (West Space). The film is in the collections of the Tate Modern and the Kiran Nadar Museum.

Afsan’s Long Day (The Young Man Was Part II), 2014, 40 min.

January 1974. Or, Autumn 1977. Now, in a Dhaka flat, historian Afsan Chowdhury writes diary entries in the form of magazine editorials. A voracious reader, he soon wearied of radicals who considered debate a waste of time; they thought the dialectic struggle could be short-circuited through the barrel of a gun. As with other times in this country’s short life, they misjudged the flow of water and history. Chowdhury uses the third person as a distancing device, and through stories of being a long-term diabetic, his time in exile (or immigration) in Toronto, and his navigation of the debris of a nation trapped by the past, he returns to the long day when he almost died. The men in uniform wanted to execute him after they found the Marxist pantheon in his library. “They thought I wrote them after I said so; I probably fit into the visual imagination of a radical. Beards are never trusted on young men. I argued with them about searching our house.” What else do you need to identify an enemy?

The narrator traverses Chowdhury’s disappointments, Sartre’s confrontation with a new Left that denied the nuances in his foreword to Fanon, and Fischer’s moment of reversal from Left pacifist clarity. The state’s overwhelming reaction made the counter-reaction inevitable; Heinrich Böll called it a “war of six against sixty million.”

The second film in the Young Man Was series premiered at Museum of Modern Art, New York (Doc Fortnight), and is inspired by Afsan Chowdhury’s diary—which also provides the series’ eponymous phrase, “the young man was … no longer a terrorist.” The accumulation of multiple memorials to the period was described by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie as a “revolutionary past meaningful in the sudden eruption of a revolutionary present” (Bidoun).

Last Man in Dhaka Central (The Young Man Was Part III), 2015, 82 min.

November 1975. The Summer of Tigers was a twilight moment for multiple Left possibilities. After the assassination of Salvador Allende, Bangladeshis worried about a similar fate. The end came much more abruptly; instead of a faceoff inside a presidential palace, soldiers surprised the guard regiment raising the national flag at dawn. A brutal massacre killed the Prime Minister and his whole family, ending the country’s first Socialist government. Three months later, two more coups followed, the last being a Maoist-inspired “soldiers’ mutiny,” which collapsed in the middle of betrayal and miscalculation. Caught up in this maelstrom was Peter Custers, a Dutch journalist who befriended the leader of the soldiers’ mutiny, and had formed his own underground group, Movement for Proletarian Unity.

Last Man unspools two stories in reversed sequences. In a series of newsreels and memos, we start at the end—with Peter’s release. In the parallel story being told by Peter, his memories unravel over books, magazines, and clippings in his Leiden home, far away from the Bangladesh of 1975 or today. Peter, like many European Leftists of his generation (especially post–Herbert Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man), believed that even if the alienated masses trapped inside modernity were numbed into obedience, the revolutionary spirit might still be found “outside” modernity—in the prisons and ghettos of the First World, or in the cities and villages of the Third. It was a search for the latter that led him to drop out of a Ph.D. program at Johns Hopkins and move to Asia in 1973. As he found out, though, there was never a complete outside; a numbed proletariat could also doom Leftist uprisings in the vaunted Third World—as Godard also hinted in La Chinoise (1967).

Last Man premiered at the 56th Venice Biennale, in “All the World’s Futures” curated by Okwui Enwezor. The film intended to begin a long-term dialogue with Peter, but has now become an unintentional memorial: a few months after watching the film in Venice, Peter was making plans to fly to Lisbon for the festival premiere when he passed away unexpectedly. The film now speaks into a void; its last man has finally said goodbye.

The Young Man Was series has been supported by Creative Capital, Creative Time, Puffin Foundation, Franklin Furnace, Rhizome, Arts Network Asia and a Guggenheim Fellowship. The three films screened together in the program I don’t throw bombs, I make films at DocLisboa 2015. The current iteration at VOX is organized by Experimenter (Kolkata) and LUX (London).