Sanaz Sohrabi

Extraction Out of Frame

2023.01.14 - 03.04

In this new exhibition created especially for VOX, Sanaz Sohrabi traces the colonial imprint left by petromodernity and the political ideologies and cultural imaginaries that have been reconstructed around the extraction of crude oil in Iran.

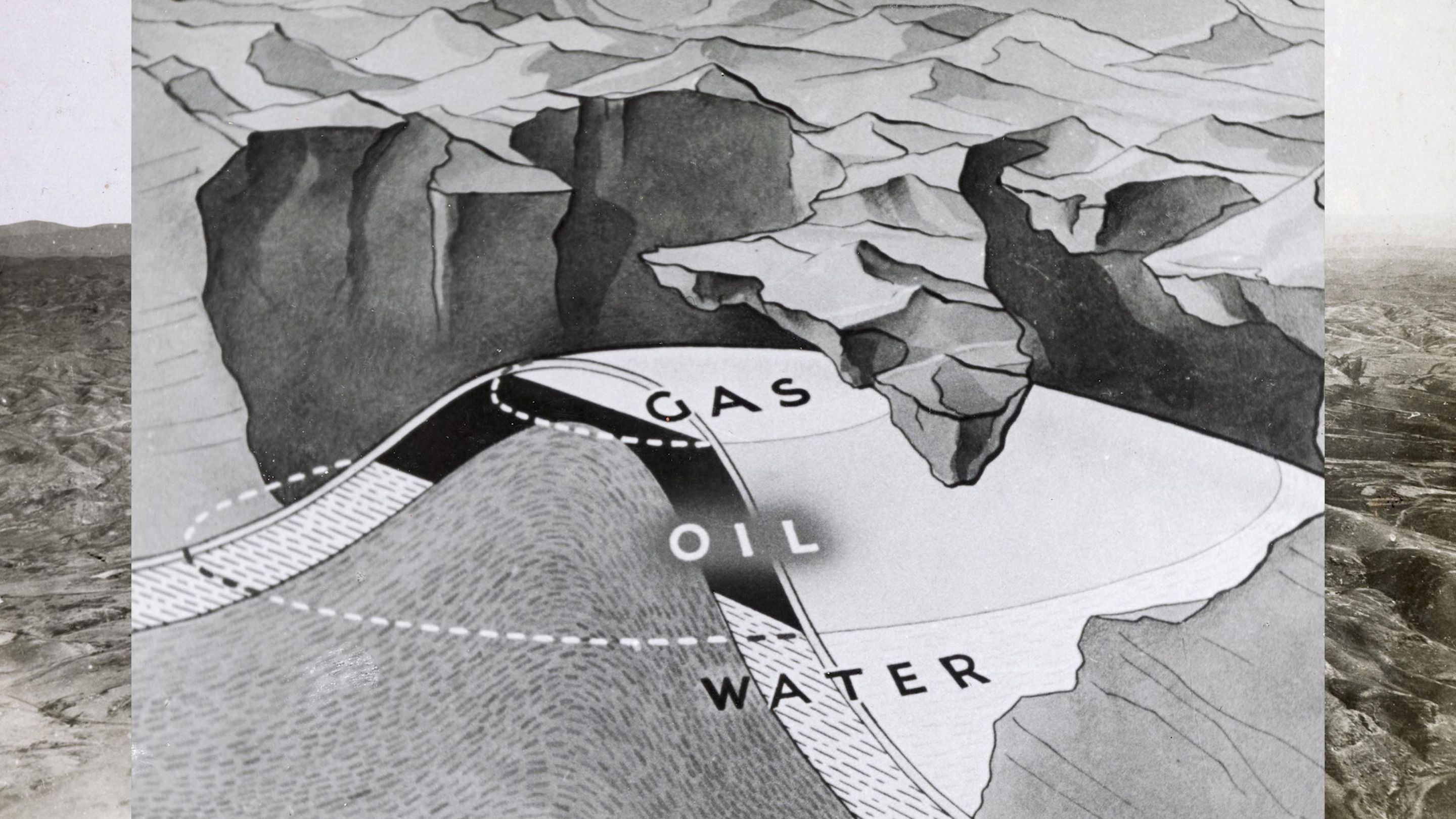

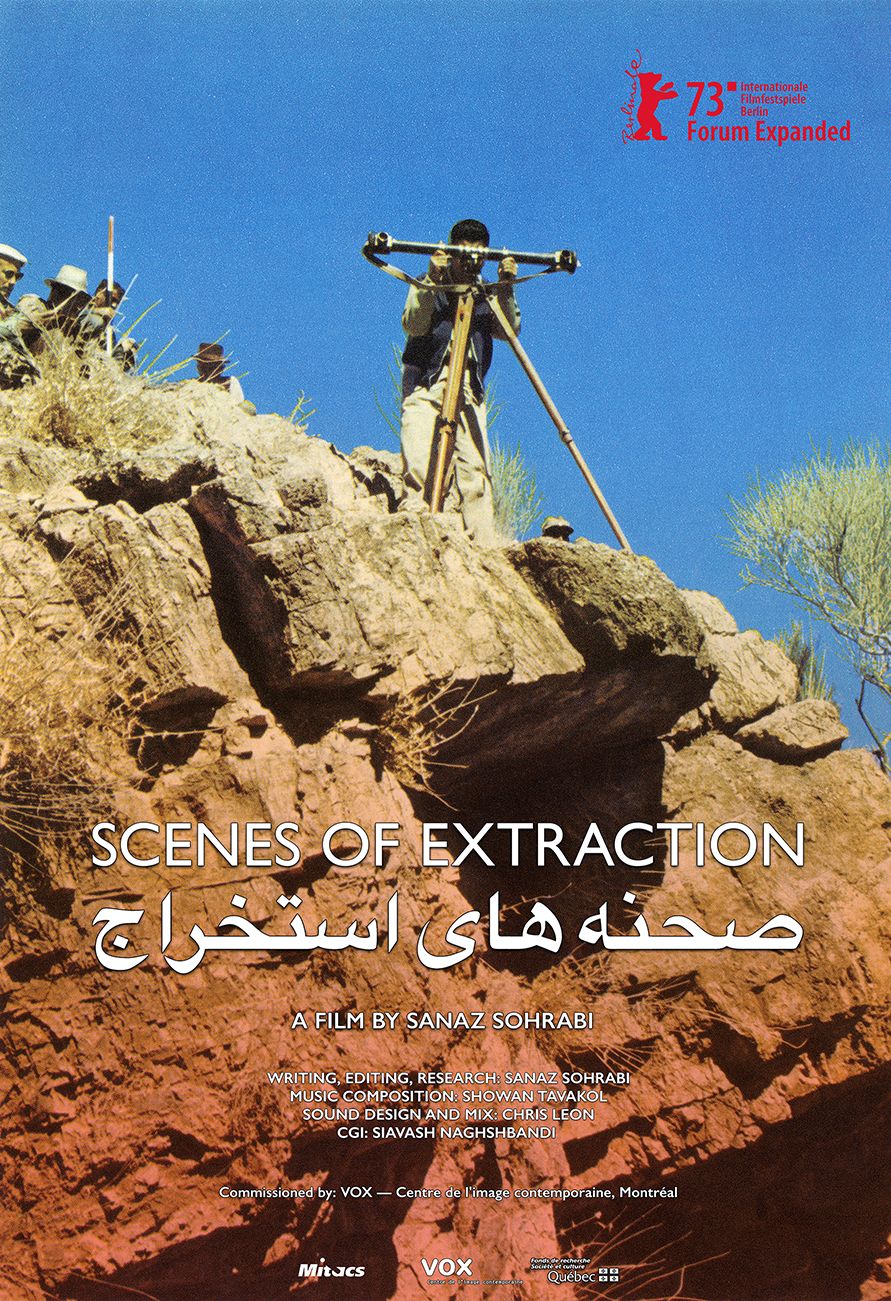

Extraction Out of Frame is the outcome of the artist’s recent research in the archives of British Petroleum. The company played a frontline economic and identity-shaping role in Iran, ushering in a certain ideal of modernity in the country before being nationalized in part. The essay film Scenes of Extraction | صحنه های استخراج (2023), the second instalment of a trilogy, renders visible the political function of imaging technologies in BP’s geological investigations. Seismic prospecting techniques, filmed documentation of boreholes and aerial photography, geological studies and topographical surveys—here modelled in 3D—reveal the stigmata left by the extractive industry on Iran’s landscape as well as the communications strategies behind this abundant documentation. Using previously unseen archival materials, the artist uncovers the traces of a system that dispossessed Iranian resources and identity.

With this exhibition, VOX is inaugurating a new research axis that explores the potential offered by imaging technologies to conduct investigations into allegations of human rights violations or colonization processes, or to support social or environmental justice causes.

NATASHA MARIE LLORENS

Sanaz Sohrabi’s work is composed with visual material drawn from the archives of British Petroleum, consulted over the course of her doctoral research and artistic practice. Through careful juxtaposition of documents and the reconstruction of historical narratives, Sohrabi proposes that the camera is an extension of oil’s extractive infrastructure, especially during colonial periods in countries such as Iran and Burma. The camera documents a gradual accumulation by geological survey teams of knowledge about that which lies beneath the surface of the earth, but it also makes the land and its people visible within the frame established by BP as a colonial agent. People no longer live in the spaces captured by photographic technologies; they populate the surface of rocks saturated with petroleum.

Central to Sohrabi’s presentation is a new film commissioned for the exhibition entitled Scenes of Extraction | صحنه های استخراج, which depicts the early exploration of Iran’s oil concession to BP signed in 1901 alongside images of the construction of Iran’s first national railroad and documentation from exploration sites in colonial Burma. In one scene, for example, the artist makes two archival photographs from the 1930s collide. The first depicts a large open workshop with roughly a hundred Iranian men busy at various worktables. Some of the figures look up at the camera and some continue with their tasks, giving the impression of a staged group portrait. Everyone is busy producing the hundreds of thousands of railroad ties necessary for the Trans-Iranian railway. In the next shot, Sohrabi cuts thirty of these workers out of their photographic context and layers them into a shot of the landscape through-structured by the railroad’s newly laid parallel steel tracks. Her intervention imagines artisans transported to inspect the result with the same care they poured into forming the ties from raw wood in the workshop.

As Sohrabi explains in the voiceover, the railway was the first major infrastructure project to be completed using oil revenue paid to the state by BP. Its construction was carefully documented by the Iranian government and represented to the public as proof that foreign control over parts of the national territory was necessary part of nationalist modernization. Sohrabi’s shift from BP’s use of exploratory technology to the Iranian government’s use of the camera reveals a continuum between BP and Iran nationalism. The project of modernization implicates both in the transformation of perceptions of extraction.

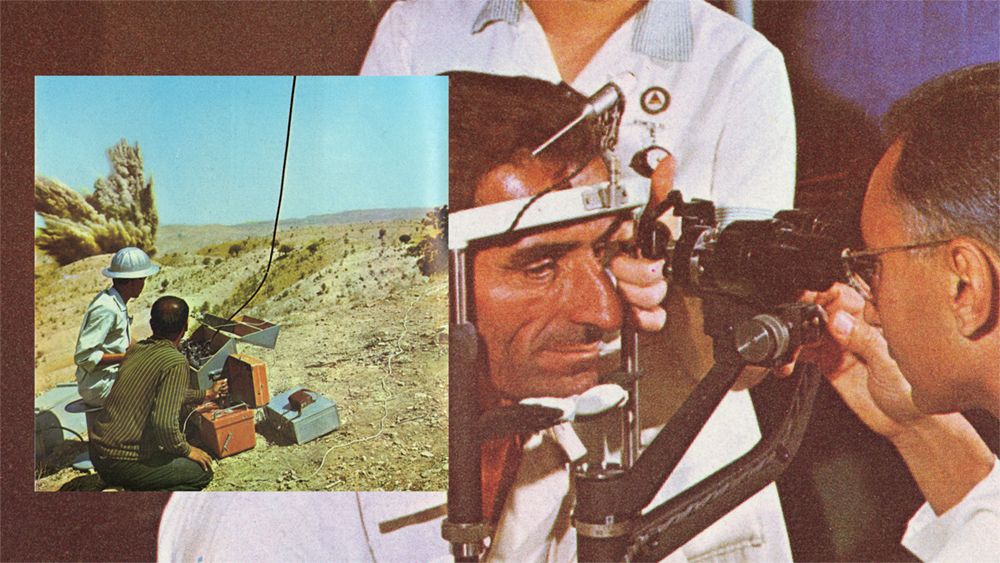

Several archival elements deployed in the exhibition extend this continuum, such as film footage shot through a camera designed specifically to descend into oil wells to check structural integrity, scientifically annotated photographs of a “borehole” camera prototype made for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1935, images of the cinema room, and a large photographic installation manned by two Iranian technicians. Sohrabi foregrounds visual infrastructures as manifestations of an extractive aesthetic, rather than as mechanical tools. The oil-well camera footage is especially remarkable in this sense, as it manifests an ultimate fantasy about the penetration of the land by visual technologies. In one clip from the 1980s, the camera pans along the shaft of the spear-like insertion apparatus. Then the scene cuts to a video editing suite, where a man’s hand is shown pushing a videotape into a machine, bringing to light the camera’s slow descent into the oil well. Produced by Halliburton–an American multinational corporation specializing in hydraulic fracking technology and operations worldwide–the video represents the conclusion of Sohrabi’s representation of colonial visuality through the development of the camera. The deeper the camera goes, the more total its logic becomes in terms of an imagination of territory.

Sohrabi’s installation remains focused on the structure of the image produced by this logic, rather than the evidentiary quality of the archive–a fact clearly demonstrated by the large colour reproduction documenting the use of a geo-camera at the entrance to the exhibition. The image was first published in a promotional magazine using offset printing matrices. Sohrabi reproduces it in her installation at a scale close to that of the body to render this structural texture. Imposing and enigmatic, the photograph stages the collapse between landscape, oil exploration, and the camera. The vivid colour contrast was intended for a mass print medium; by reproducing it at this scale, Sohrabi denaturalizes the medium’s aesthetic conventions. By systematically folding the photographic image together with apparatus and juxtaposing infrastructure and the body at key historical junctures, Sohrabi renders the construction of extraction’s imaginary–she makes it palpable and strange.

2023 Berlinale

The essay-film _Scenes of Extraction | صحنه های استخراج_ by Sanaz Sohrabi will also be screened as part of the Forum Expanded de la Berlinale 2023.