The Radical Imaginary: The Social Contract

2018.09.13 - 12.15

- Notes

Reading room

Nina Beier, John Boyle-Singfield, Étienne Chambaud, Maria Eichhorn, Andrea Fraser, arkadi lavoie lachapelle and Jean-Frédéric Ménard, Kelly Mark, Nadia Myre and Discriminating Gentlemen’s ClubThe artist, the law and the contract

The artist contract has existed since the Middle Ages. Originally, its purpose was to clarify the respective responsibilities of artist and patron in developing a work. Today, the nature of the artist’s work has become an issue unto itself. It has been transformed such that it has complexified the status of the artwork and, in turn, its legal purpose: the artist is the owner of their work, which they can sell, and the production of which may be entrusted to a third party; the artist is a worker, who may be compensated for producing a specific project for an institution or a collector; the artist is also a knowledge worker who may claim authors’ rights to the design and distribution of their work.The reading room presents historical and legal documents, essays and other works about the artist contract and authors’ rights (copyright), along with works that subvert the uses of such.

The Radical Imaginary: The Social Contract is the first project in a series of exhibitions about the Institution and its history, seeking to understand how artists have either associated themselves with or been opposed to it, gradually inflecting its positions. The objective is to observe an alternative form of institutional critique that conceives of the components of the Institution (the judicial system, the university, the economy, etc.) as processual forms, in constant transformation.

The judicial system is the institution studied in this initial component. The artworks presented call into question legal tools and concepts—rules, procedures, contracts, jurisprudence, trials—so as to understand how they act upon art, its system and its players, while altering the rules of the social game. The artists not only appropriate the apparatus of the legal system, exposing its ethical and political dimension, they also study the unseen codes governing it: for example, issues around intellectual property, which are inexorably transforming their work and the institutions in which they have agency.

MARIE J. JEAN

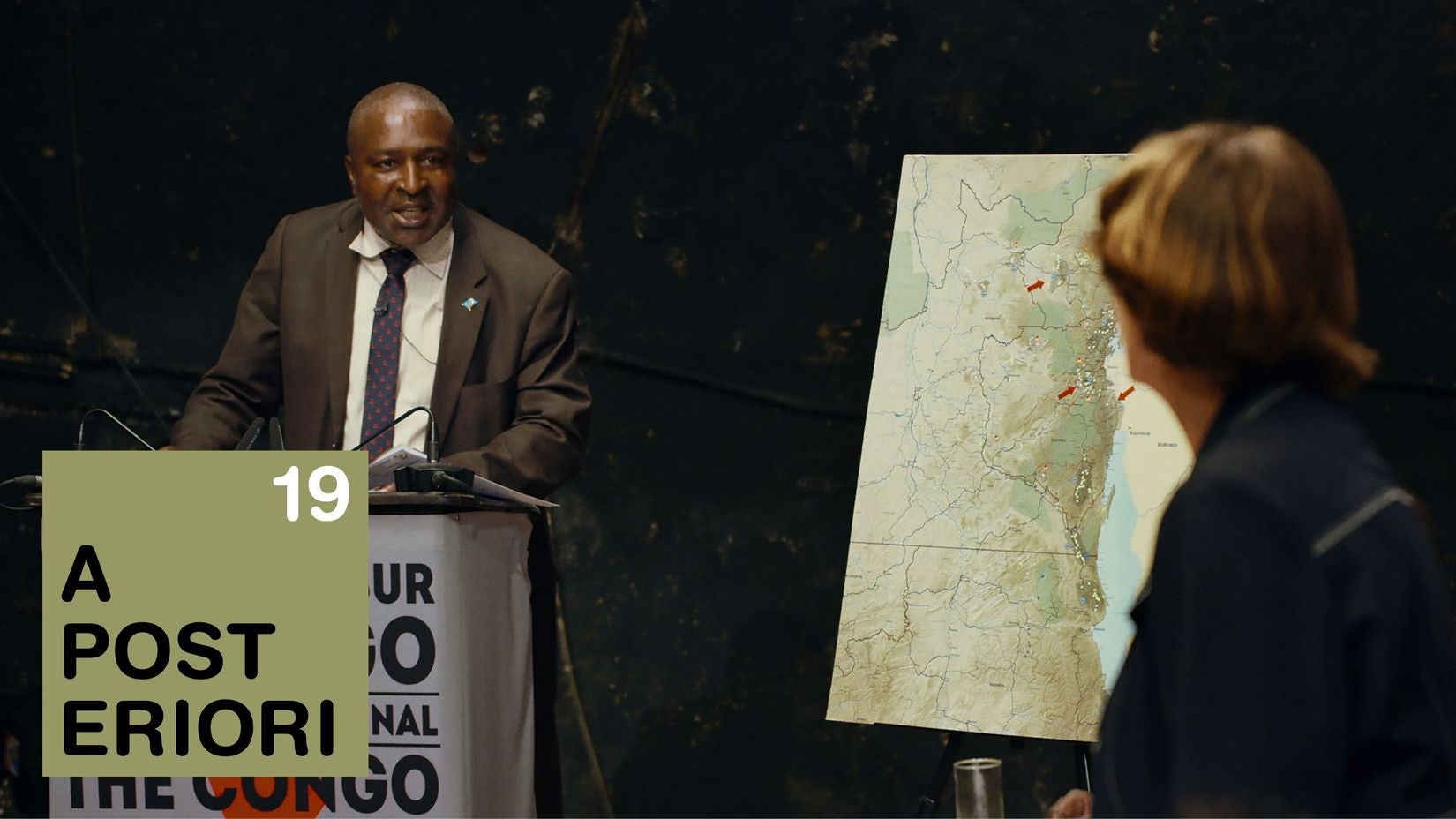

Believing that the International Criminal Court had shirked its duty in the matter of the Congo’s twenty-year-long civil war, Milo Rau decided to mount a tribunal in Bukavu, at which lawyers argue and victims, witnesses, executioners would testify, along with members of the government, the army, rebel groups, and NGOs—all of them real-life protagonists in this ongoing human tragedy. For, despite the fact that the conflict has claimed more than six million lives, the Congolese today remain trapped in a state of impunity, because none of the war crimes committed has been subject to legal challenge. What prompts an artist to stage this type of work, appropriating the conceptual and political apparatus of the judicial system? Rau is categorical: his theatre does not aim at “sterile criticism of policies or institutions”; it seeks nothing less than to “change” them. Yet although the trial was heard using actual testimonies—the protagonists played their own roles before 1,000 spectators who had come to hear them—it had no legal force. Its repercussions were considerable, however, because The Congo Tribunal (2017) has demonstrated that this barbaric conflict resulted from exploitation of natural mineral resources—gold and coltan—by multinationals that desire the status quo in this region of Africa so as to better profit from growth in a technology industry (mobile telephony) in a globalized economy.

The Congo Tribunal points up the lack of international judicial institutions and effective economic regulatory structures to safeguard justice and rights for the Congolese. If Rau employs the form of the tribunal, subscribing to its operational logic, it is to generate a “radical imaginary,” as posited by Cornelius Castoriadis: that is, a process of continuous creation that produces novel significations of the imaginary with the potential to transform institutional positions. The radical imaginary thus impels the emergence of open knowledge, continually in the process of generating itself, out of two movements that are generally in a relationship of mutual tension: on the one hand, the requirement for “critical lucidity,” and on the other, the “creative function of the imaginary.” It is a process whereby the individual, creating and constantly drawing forth new critical stances and new realities, is him- or herself transformed by what s/he modifies and, consequently, the boundaries of the institution in which s/he has agency are modified. All of the artists featured in this exhibition submit Justice to a comparable radical imaginary, casting a lucid gaze upon its ethical and political implications.

This exhibition is presented with the kind collaboration of the LABOR gallery, Paula Cooper Gallery, the Collection of Patrick and Lindsey Collins, the Walter and McBean Galleries of the San Francisco Art Institute, the Warkworth Institution, MAGNETFILM, Pointe-à-Callière, Artexte, Lisa Bouraly and Beat Raeber, Galerie.

VOX joins forces with the Montreal International Documentary Festival (RIDM) to copresent two movies of their 2018 edition! These feature-length films go hand in hand with both themes and artworks from the exhibition The Radical Imaginary: The Social Contract.

Stealing Rodin (2017) by Cristóbal Valenzuela—on the theft of a famous sculpture by a young arts’ student and the unusual trial that ensued—will be presented on Friday, November 16 (Cinéma du musée at the MMFA, 5:00 p.m.) and Sunday, November 18 (Cinéma du Parc, 6:15 p.m.).

The Proposal (2018) by Jill Magid—whose installation of the same title is shown until December 15 at VOX—will be presented Friday, November 16 (Cinémathèque québécoise, 4:30 p.m.) and Saturday, November 17 (Cinéma du Parc, 8:15 p.m.).