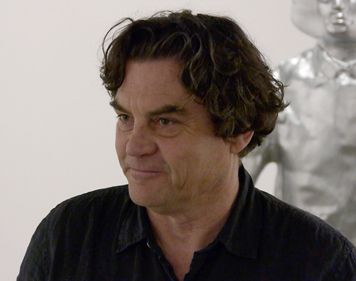

Trevor Gould. Philosophy’s Self Image

2012.09.07 - 10.13

DOMINIQUE FONTAINE

The exhibition of recent works by Trevor Gould brings together sculptures, watercolours and a video. As a group these works offer new insight into Gould’s recent practice and, particularly, the expanded choice and themes and methodologies he uses to further underline our sense of humanness in relationship with nature.

The 19th century, in Western Europe and North America, wrote John Berger in Why Look at Animals ? 1, saw the beginning of a process, today being completed by corporate capitalism, by which every tradition that was previously mediated between man and nature was broken. Inspired by 19th-century artworks and Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, Trevor Gould’s Philosophy’s Self Image draws parallels between Darwin’s inductive method of scientific investigation, whereby close observation and the collection of purely descriptive data precludes postulation, and the formation of a hypothesis. The exhibition also refers to the allegorical convention of Western painting traditions that place animals in human contexts and contemporary cultural displays. Hugo Rheinhold’s statuette Darwin : Eritis Sicut Deus (“Darwin : you will be like God”), also known as Affe einen Schädel betrachtend (“Monkey regarding a Skull,” aka “Darwin’s Monkey,” [1892]) and paintings by Gabriel von Max illustrate Gould’s critical exploration on the relation of man and animal.

Philosophy’s Self Image suggests a new trajectory for Gould and fosters a significant stage of his practice. While much of Gould’s early work focussed on the appropriation of exhibition techniques—such as diorama, taxidermy, theatrical presentation and archival documents—to critique our relationships to nature, his recent works reflect on cross-species spaces of interaction as a philosophical attempt to make sense of what, as humans, we are and how we relate to the world.

In 2011, Gould presented an installation called Balancing Act in the orangutan exhibit of the Toronto Zoo where the starting point was a reflection on time (past, present, future) and an experiment with site and space. The interspecies installation creates a contact zone, a mode of engagement with the orang-utans. Using allegorical sculpture elements, Gould staged an installation to gain access to the world of the animals in the zoo as an attempt to understand what interests them, what affects them, and what motivates them. An integral component of the exhibition is the video documentary resulting from the Balancing Act installation, in which we see orang-utans interacting with sculptural elements. This video allows us to explore what could be called an animal phenomenology. It offers a different approach on interspecies relations and thus invites the viewer to consider human-animal relations from a different perspective.

Gould interest in philosophy forms the basis for the works in Philosophy’s Self Image. As in his previous work, a prime concern is the interior mapping that guides and mediates our actions and our sense of presence in the world. From the constructive process to interpretative explorations, his work focusses on recurring themes such as appropriation, power and representation. His work thus problematizes our awareness and understanding of cultural space. As such, Trevor Gould’s work can be interpreted as an exploration of the way images and objects represent the beliefs, attitudes and values in our social history.

As in the previous body of works, the new corpus embodies Gould’s commentaries on the transfer of cultural patterns and the appropriation of form, or a point of view from which to contemplate world geography, history and traditions. The recurring motifs, like the ape, serve as a metaphor for geographical locations and represent the domination of one culture over another. In most of his installations, Gould has appropriated exhibition apparatus and, in so doing, questioned the role of the institution and persistent imperialist symbols. Through this work, he has drawn on the symbolism of various flora and fauna, evoking a nature/culture relationship in order to explore issues of colonialism, post-colonialism and identity formation. The zoo, which represents one of the last monuments of 19th-century public colonial power, is a good example of the way we mediate our relationship to nature.

Beyond the way we think of our relationships to animals and the particular way we enter their world, Gould invites us to think and to feel from another point of view, and thus to question and reflect aesthetic as well as artistic questions in political dimensions. As the French philosopher Jacques Rancière highlights in The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, the categories of the aesthetic and the political are connected through the sensually perceptible:

“I call the distribution of the sensible the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it. A distribution of the sensible therefore establishes at one and the same time something common that is shared and exclusive parts. This apportionment of parts and positions is based on a distribution of spaces, times, and forms of activity that determines the very manner in which something in common lends itself to participation and in what way various individuals have a part in this distribution.” 2

1. John Berger, Why Look at Animals ? (London: Penguin Books, 2009).

2. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill, London: Continuum, 2006 (first published as Le partage du sensible : esthétique et politique, Paris: La fabrique éditions, 2000).