Miles Rufelds

A Hall of Mirrors

2026.01.16 – 03.28

- Notes

The feature film It’s Not Brakhage (54:39) is screened in a loop and restarts at the following times: 11:00 a.m. // 11:55 a.m. // 12:50 p.m. // 13:45 p.m. // 14:40 p.m. // 15:35 p.m. // 16:30 p.m.

In an age when every visual and informational production is put under the microscope of truth, when conspiracists and whistleblowers share the same platforms, what is the artist’s role in pursuing, accumulating and disseminating facts? Drawing on film noir tropes while deploying visual essayism as an investigatory mode, Miles Rufelds reconciles authenticatory images with deceptive illusions around a legendary figure of experimental film.

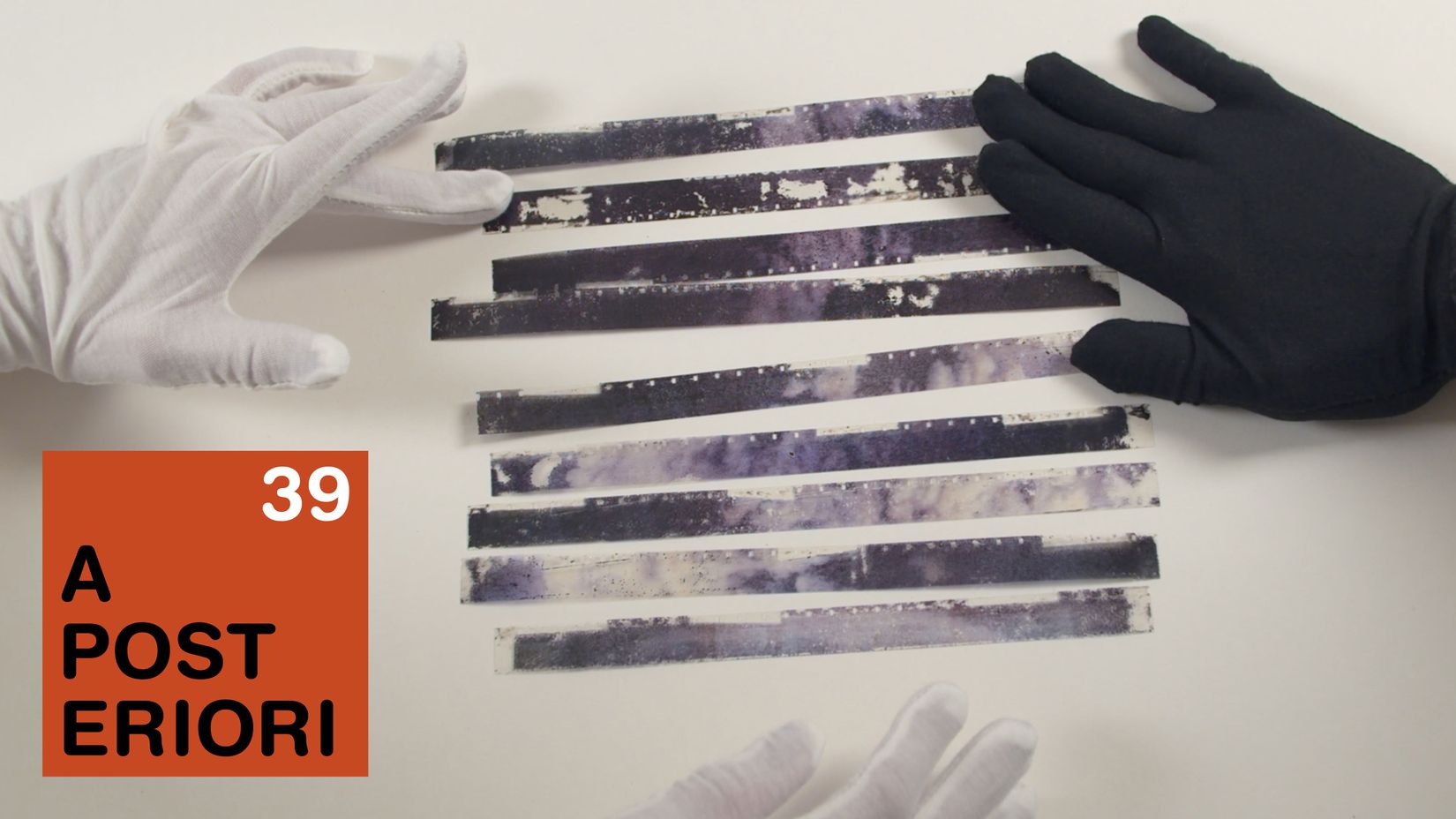

In the parafiction film It’s Not Brakhage, an investigator-researcher in the throes of doubt delves into the archives of a mysterious foundation with links to the DuPont industrial dynasty. His search reveals a network of connections in which cinematic experimentations, image technologies, the arms lobby and family fortunes intertwine. As the narrator is gradually gripped by feverish speculation, the quest for the truth becomes suspect as well.

Archive Noir: Chemical Darkness and Autogenic Light

JON K SHAW

Surely the once fertile grounds of automythography, tricksiness, counternarratives and bootstrapped realities have been exhaustively ransacked of their utopian urges and heterogeneity? Led by politicians who no longer even pretend to care if we know they are lying, how can it be anything but perverse to defend the muddling of fact and fiction?

As with Miles Rufelds’s earlier work concerning the DuPont company, It’s Not Brakhage knows a hard fact when it sees one. It comprises expansive and rigorous research, not only into the characters and court cases that make and mar the company’s history, but into the materials and industrial-chemical processes through which it forms our everyday lives. As an indictment, Rufelds’s film recalls Hans Haacke’s classic of forensic accounting Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. Where Haacke impeaches art’s institutions over their complicity with the grubbiest practitioners of rentier capitalism, Rufelds asks how we can also reflect our positionality, our own complicity, when our materials, institutions and funding streams all enmire us in ecological, financial and social inequity.

Our narrator in It’s Not Brakhage is openly uncomfortable about having forged a connection with the Foundation where this enigmatic artefact, these two-thousand-six-hundred-odd frames of film, are housed. This is perhaps his most explicit act of identification with Stan Brakhage: both have had their price met for art-laundering DuPont. One, needing the cash, takes a paycheque for organizing a festival of experimental, cameraless film to promote commercially flopping film stock; the other, needing “the Truth” about Brakhage’s abandonment of the festival, takes the inaugural slot of an archive residency in the belly of the beast. Having decisively concluded, minutes into his film, that the archive’s “lost Brakhage” is misattributed, our narrator’s deeper agenda emerges: Who actually made it? How is it connected to Brakhage’s death? Film history has become conspiracy theory.

Yet our narrator is, for a conspiracy theorist, curiously unmarked by zealotry. His investigation roots for some conclusions, but with little ceremony and, in the end, not that much proof. As the research continues, we observe the odd situation of questions being resolved and him becoming increasingly disoriented within the investigation. Morally directionless yet still embedded in the big bad Other that is DuPont, our narrator could be forgiven for succumbing to a defeatist torpor or noir paranoia.

Yet, having answered a number of his questions to his own satisfaction—unburdened of the burden of truth—we find our narrator turning toward something more like speculation, even re-enchantment. This is work undertaken, in the end, with scissors and light table and film; which is to say, through what he will later call, apropos the “lost Brakhage,” “practical research.” No longer oriented toward determinations of Truth, any clean cuts made between fact and fiction are now most interesting for what possibilities they engender; for their recombining elements into new constellations, producing new perspectives, testing ligatures and, ultimately, fostering speculation—this last understood not as nihilistic uncertainty regarding what might be true, but as an under-determined, more protean sense of what might be possible.

For Brakhage himself, such convulsions of possibility were particularly potent at the intersection of colour and sound: their unexpected, indeed unforeseeable, reciprocal sparks and the resonance of these with the nervous system of the viewer in a “streaming of shapes that are not nameable—a vast visual ‘song’ of the cells expressing their internal life.”1 It is this deeply organic notion of vision that his ever-inventive films sought, making of the apparatus an extension of inner experience.

This kind of “hypnagogic vision” and “closed-eye seeing” gained particular importance for Brakhage around the birth of his children, the period in his life that the festival coincided with. And it is family and the importance of sound–light resonances that our narrator ultimately finds to be key to the DuPont story, through the figure of Mary Hallock, inventor of the Sarabet colour organ and mother of Crawford Greenewalt, president of DuPont from 1948 and commissioner of the abortive cameraless film festival.

With the conjecture that the “lost Brakhage” is, in fact, Hallock’s work, and echoing the Swedenborgian and (hence) Theosophical roots of her sound-and-colour experiments, our narrator tells us how he has come to understand that the film explores “the material affect of images or sounds / not as inert symbols but as immanent forces.” This is done through playing on the “correspondences between them” and “the consequences of their scission.” As becomes clear, the envelope of correspondences and scissions between Brakhage and Hallock—and, indeed, our narrator—itself attains the level of an event. Little matter who made the film or what consequences visited Brakhage; here, we find all three practitioners seeking to “escalate art forms well beyond entertainment, towards something like practical research.”

And it is here, I would argue, that we find reason for insisting on the importance of continuing to work with matrices of fact–fiction. Not to undermine shared, factual understanding of world affairs, nor to continue the vaporization of any notion of consequences for those in power. Rather, it is to find new correspondences, to try things out, to engage in practical research that does not seek to determine veracity—or rather, does not capitulate to the will to truth as an end in itself—but seeks to create possibilities. It is such experimentation which positively blurs fact and fiction, allowing for productive correspondences and scissions across the two through which counternarratives can be asserted and, perhaps more importantly, our bodies can vibrate more intensely and on new frequencies. It is such wonders that conspiracy theory more widely has lost sight of, fixated as it is on control and fakery, its Deep States and Flat and/or Hollow Earths. We can certainly analyze the DuPont company in terms of knowledge withheld and the power networks behind it; but, as Rufelds’s film avers, we must also remain alert to what lies further out and further in.