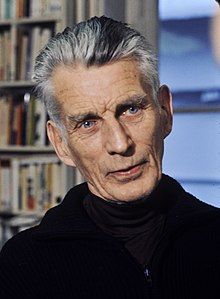

Samuel Beckett

2007.11.03 - 12.15

ÉTIENNE FORTIN

“When I first read Not I, I burst into tears. The text had an extraordinary emotional impact on me. I immediately felt it should be read very quickly. […] Beckett and I focused our attention on the rhythm, the screams, the breathlessness, and so on. But I never asked him what the play meant. The first time I rehearsed it, I fell apart. I had the impression I no longer had any body; I had no more reference points in space. […] I really had a feeling of falling forever.”1 This is how Billie Whitelaw summed up her first contact with Samuel Beckett’s theatrical text entitled Not I in English and Pas moi in French. The play, transposed for television by the author with Whitelaw in the role of the single character, named “Mouth,” tells of that fatal fall of a human being whose self-questioning fritters away and whose quest for meaning aborts into infinitesimal, “tiny little things.”2 Beckett had already used the atrophied human body as a metaphor for psychic disintegration in the final two volumes of the narrative trilogy Molloy (1948), Malone meurt (Malone Dies, 1949) and L’Innommable (The Unnamable, 1949), in which a man-torso analyzes his world through his failing senses, and a head-egg no longer has any idea of what it speaks.

In Not I the human being, here a woman, no longer has any body at all. All that is left of these human remains is a mouth—a speech organ that, though it strongly senses the urgency of speaking, is no longer able to do so comprehensibly. In the play, “Mouth” sits in an empty space, surrounded by blackness, plunged into the void of a stripped-down space; in the film Beckett used a close-up, bringing us much closer. To further underscore the sense of exhaustion and deterioration, Beckett shot the film in one long take, without cuts, lasting the entire length of the text uttered by “Mouth”—approximately twelve minutes. Not I flings us into the midst of an unremitting logorrhea, an unbridled soliloquy. We are fastened to the strange world of these lips that doubtless once belonged to a woman… of this mouth that doubtless once was. Whitelaw is stunning as she gasps, inspires, expires and breathes this dramatic poem. Increasingly chopped, syncopated, moving from whisper to whisper, the mouth, lips, teeth and tongue depicted in extreme close-up, the repeated screams, shouts of “What?” and questions issuing from this organ filling the screen, suck us into a maelstrom of words that clash, complement each other and cancel each other. A powerhouse showcase for the actress, an intense viewing experience for the public, and a text at once disturbed and disturbing, Not I is not only a privileged glimpse into Beckett’s artistic intent, but also evidence of the tragically beautiful universe he posited within his creative process.