Lého Galibert-Laîné

Kevin B. Lee

Reading // Binging // Benning

2023.11.23 - 2024.02.22

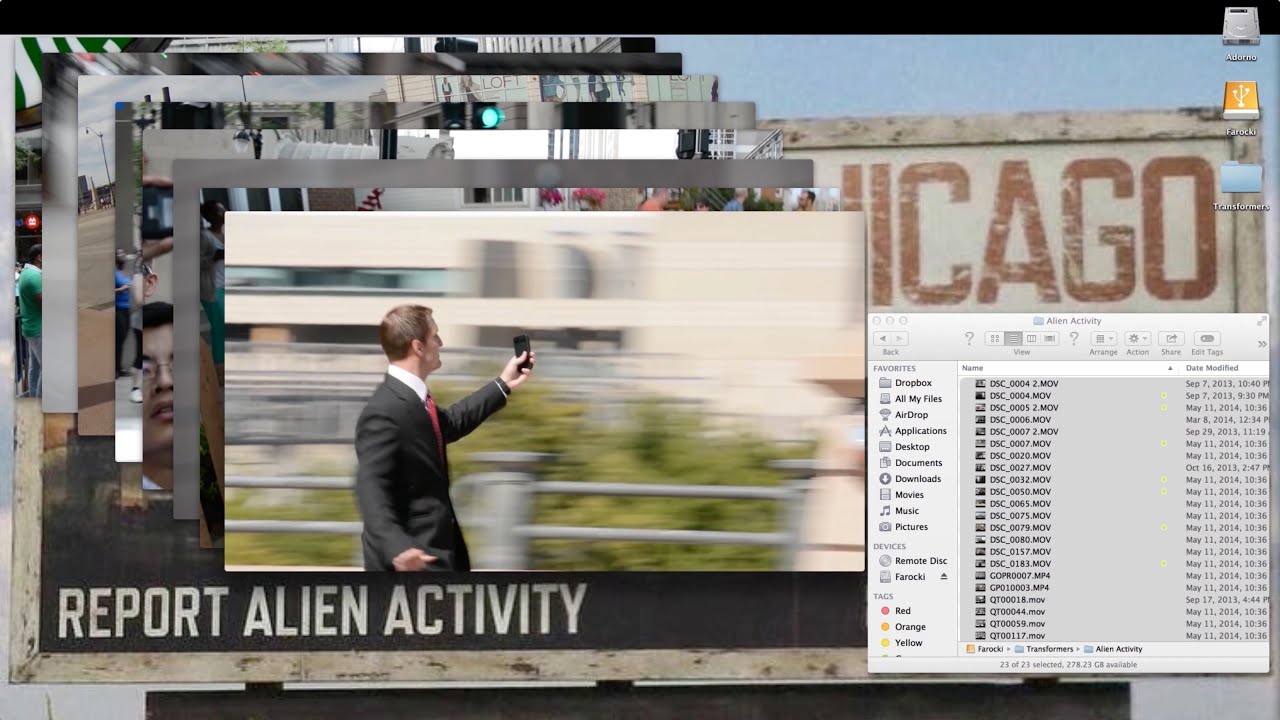

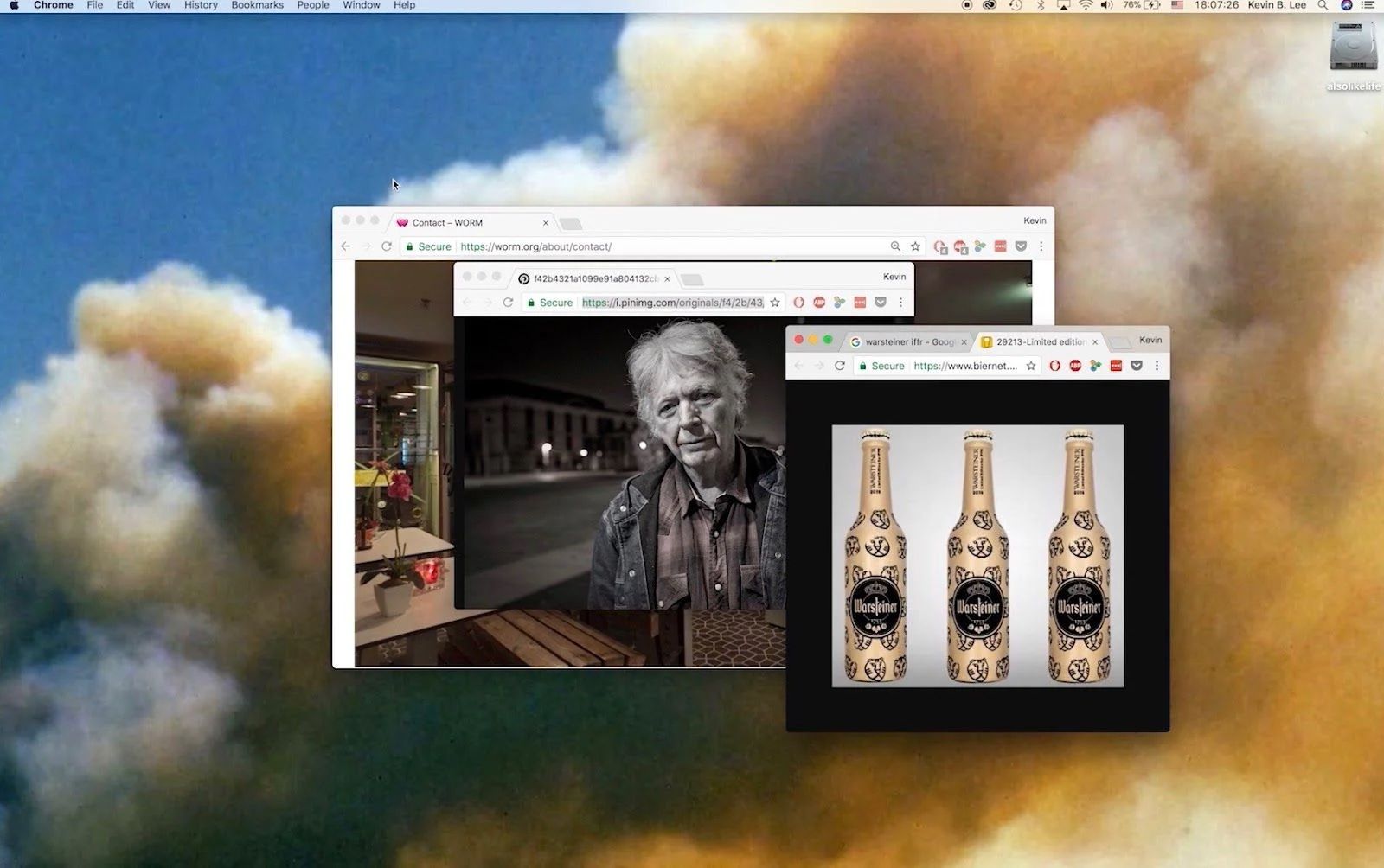

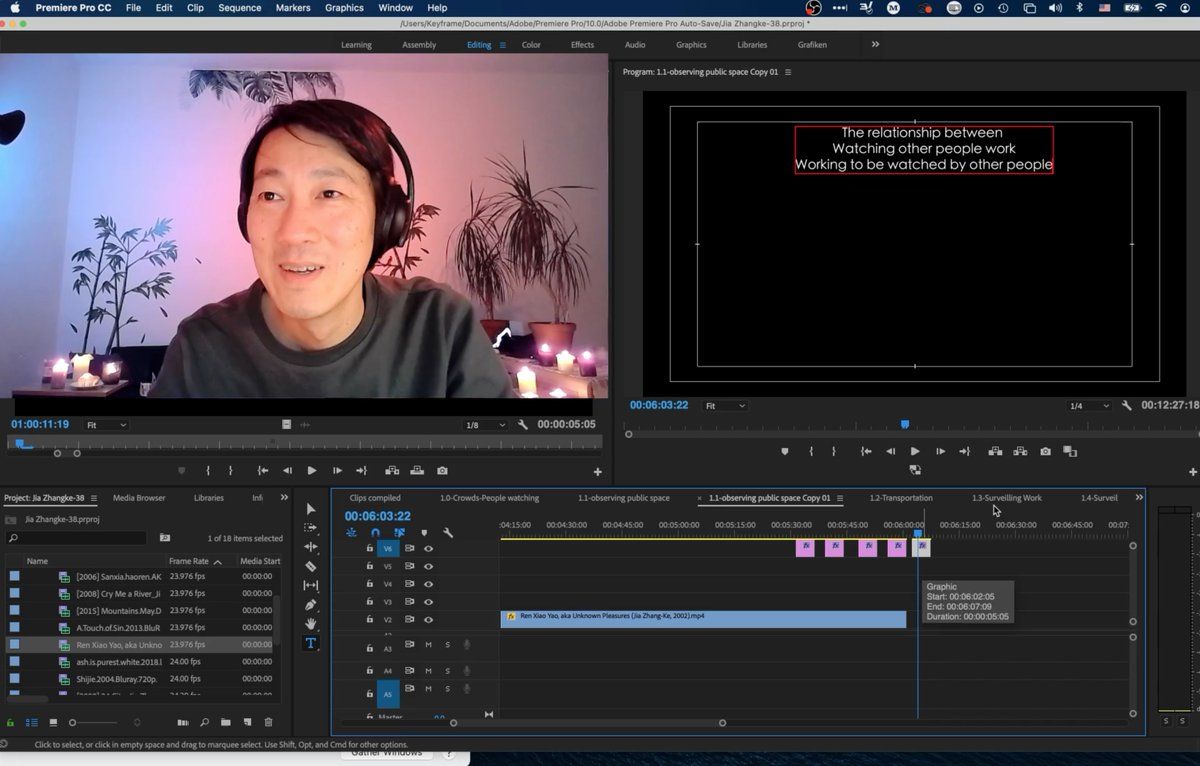

Reading // Binging // Benning is a speculative video essay that examines James Benning’s film Readers (2017) and raises the question: how much can you see of a movie you haven’t seen? Through a bold and innovative desktop documentary approach, filmmakers Lého Galibert-Laîné and Kevin B. Lee propose a meticulous investigation of the visual, sound and narrative components of Benning’s work.

The Video Essay [extracts]

KEVIN B. LEE

“I produced my first video essay 15 years ago, enabled by the circumstances of that moment: the unprecedented accessibility of digital tools for ripping, editing, and exporting film and media content; the rise of online video platforms for publishing user-generated content (most notably YouTube); and the heyday of elaborate and individuated practices of online film criticism fueled by the blogosphere before it was supplanted by social media in the 2010s. My first video essays were conceived rather myopically as a way to advance my career as a film critic by employing an innovative audiovisual approach. But video essays quickly found their way into other contexts adjacent to film criticism. Within academia it provided a novel method of practice-based film and media studies (under the legitimising neologism ‘videographic criticism and scholarship’)1 that posed a monumental challenge to the centuries-old hegemony of academic texts. Conversely, the video essay has facilitated the operations of experimental cinema and video art amidst the larger trends of practice-based research and knowledge production that define the contemporary art-academia industrial complex.

“But to delimit the significance of video essays to innovations within criticism, scholarship, and experimental art is to miss the degree to which they have disrupted each of them as part of a profound shift that marks the first phase of 21st century audiovisual culture. Something like a Trojan horse, the video essay offered a means to elucidate cinema culture to a greater number of people, but instead folded into a larger historical transformation of cinema within emergent–and dare I say, newly dominant–audiovisual contexts. Equipped with smartphones, laptops, and social media platforms, a generation has devised its own audiovisual forms and codes that function as everyday modes of media communication. This is the latest stage of what Jonathan Beller nearly 20 years ago termed ‘the cinematic mode of production’, in which ‘cinema and its succeeding, if still simultaneous formations, particularly television, video, computers and the internet, are deterritorialized factories in which spectators work, that is, in which they perform value-productive labor’.2 Within this context, the video essay may have played a modest but distinctive part in the now constant production and circulation of audiovisual media, as a way to study and reflect upon existing film and media, and in doing so, pose the possibility of applying cinematic insights to making the movies of one’s own life.”

Extracts from: Kevin B. Lee, “A videographic future beyond film,” NECSUS_European Journal of Media Studies, no. Futures (Autumn 2021). [ https://necsus-ejms.org/a-videographic-future-beyond-film]

A Videographic Autoethnography [extracts]

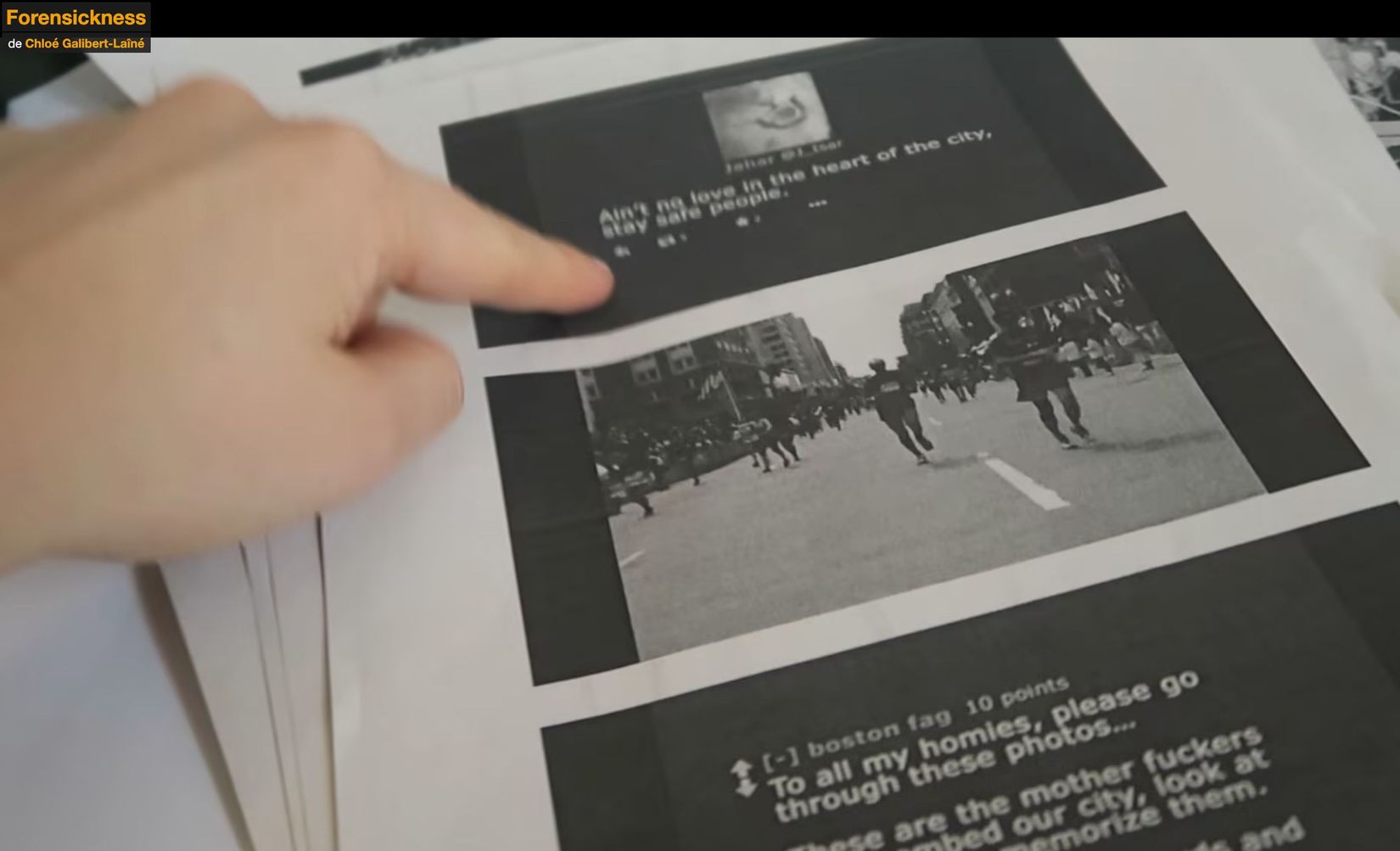

LÉHO GALIBERT-LAÎNÉ

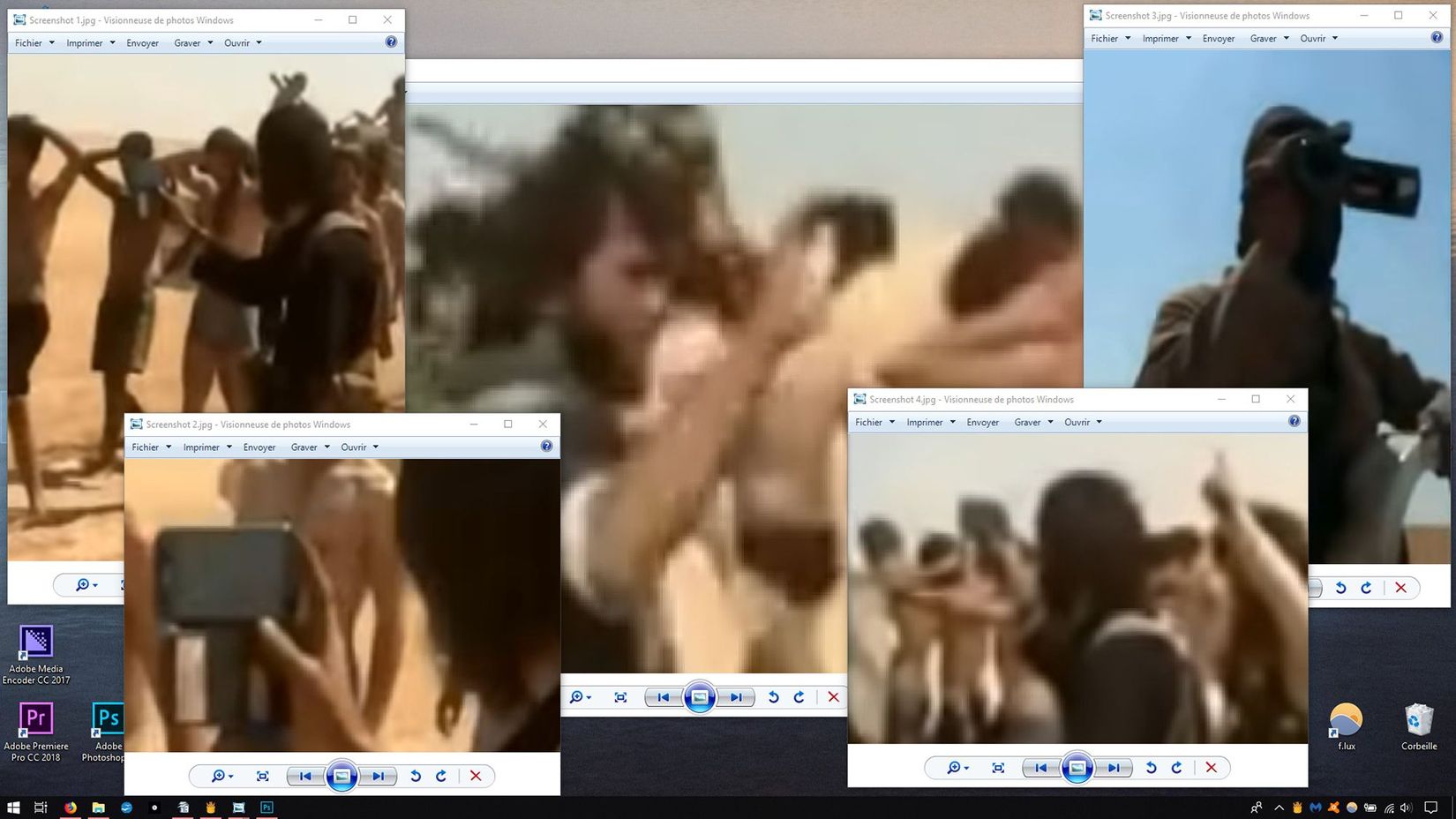

“On a methodological level, my video essay[s] can be said to draw from two existing fields. First, the field of videographic media studies, where researchers employ the audiovisual medium to produce ‘performative’ media analyses.3 The links between desktop documentary and videographic research have notably been explored by Catherine Grant, who evokes the performativity of desktop filmmaking in the following terms: ‘[Desktop documentaries] use screen capture technology to treat the computer screen as both a camera lens and a canvas. [They] seek both to depict and question the ways we explore the world through the computer screen’.4 The desktop documentary format prove[s] productive [. . .] because it allows for a very precise and comprehensive contextualization of all the presented media. Each video, image or news article that I encounter[. . .] during my research process is shown as I found it, embedded in its original interface. This makes it possible for viewers to become aware of the digital infrastructures that conditioned my access to the studied media and influenced my affective and cognitive responses to them. [. . .]

“Secondly, [my practice] also shares important features with works produced in the field of autoethnography. In their essay about the affordances of autoethnography in popular culture studies, Jimmie Manning and Tony E. Adams propose the following definition: ‘Autoethnography is a research method that foregrounds the researcher’s personal experience (auto) as it is embedded within, and informed by, cultural identities and con/texts (ethno) and as it is expressed through writing, performance, or other creative means (graphy)’.5 [. . .] Because it emphasizes ‘personal experiences’, autoethnography is a productive approach to research spectatorship [. . .]. As Christine Hine writes:

‘Through autoethnographies of online experience, we are [. . .] able to find out how standard infrastructures are made into personal experiences […]. The autoethnographer situates Internet experiences and explores the multiple ways in which they make sense. [. . .] Autoethnographic approaches, like blended, multi-sited, networked and connective approaches [. . .] follow the trails of phenomena wherever they may lead.’6

This paragraph underlines two features of the autoethnographic approach that I think are especially resonant with my video essay[s]. Online autoethnographies are said to produce accounts of how ‘standard infrastructures’, that are available for others to engage with, are experienced by a given individual. For me this allows for the production of ‘situated knowledge’7 about the way these online infrastructures determine our affective responses to the media they embed [. . .]. Autoethnographers also, Hine writes, follow the phenomena ‘wherever they may lead’: this exploratory component of the autoethnographic method is definitely something that I recognize from my own research [method. . .]. Because this experience of digital ‘flânerie’ is such an essential component of our everyday practice of online media, I agree with Christine Hine that the autoethnographic approach, [especially when associated with the desktop documentary format,] offers interesting affordances when it comes to researching [and documenting] networked media practices.”

Extract from: Lého Galibert-Laîné, “Framing Terrorist Media: a Videographic Autoethnography,” in Bernd Zywietz (ed), Propaganda des “Islamischen Staats” (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2020): 333-362 (freely translated).

Watch more video essays by the artists