Bertille Bak

Mon Sud est ton Nord

2024.09.06 – 12.07

This exhibition devoted to the work of French artist Bertille Bak comprises selected recent video installations made in collaboration with workers in Africa, Latin America and Asia affected by labour exploitation in the age of the globalized market economy.

Tracking trajectories of outsourcing, Bak encounters Moroccan craftsmen confronted by the influx of made-in-China goods, women in Morocco employed to shell shrimp caught in the Netherlands, and children working in mines in five Southern countries. In each of these immersions in various communities, the artist and the groups directly affected map out a scenario and then stage it. The workers interpret fanciful versions of their daily actions for the camera, enhanced by rudimentary visual and sound effects added by the artist at the editing stage. In so doing, Bak and her collaborators provide absurdist illustrations of the impacts of international trade on local populations, while reinjecting doses of humanity into the logistics chain.

ANAËL PIGEAT

A goat standing in a kitchen. Women in an alleyway followed by cats, a panther and a camel walking in single file. Purple and yellow chicks on moving sidewalks resembling highway interchanges. Children arranged like dolls in a cardboard box. Roses guillotined and transported in train wagons as if on their way to a concentration camp. Planes flying in a heart formation. Such are the scenes on view in Bertille Bak’s faux-cheerful, implicitly dire videos, which cast tragedies as friendly neighbourhood entertainments. Born in Arras, France, in 1983 to a family of miners originally from Poland, Bak has earned acclaim over the last twenty years with exhibitions in such venues as the Centre Pompidou, the Jeu de Paume and the Louvre-Lens.

Her video imagery frequently problematizes currents that traverse the entire planet–sometimes positive, but so often terrifying when unchecked. Boussa from the Netherlands 1 (2017) is a fable about global commerce: shrimp caught in The Netherlands are shelled by women workers in Morocco, then shipped back to The Netherlands to be sold there. In filming her “models,” workers she meets in the field, Bak enlists them in collaborative efforts that recompose, in unison, their own situations via imaginary scenes away from their place of work. And while these pieces speak of the contemporary world, their documentary aspect is of course illusory. These international fluxes are also visible in 2023’s Nature morte, in which cut flowers merrily flow across borders that are impervious to workers, to be used out of season for absurd celebrations that have more to do with the siren songs of consumerism than to communion between people.

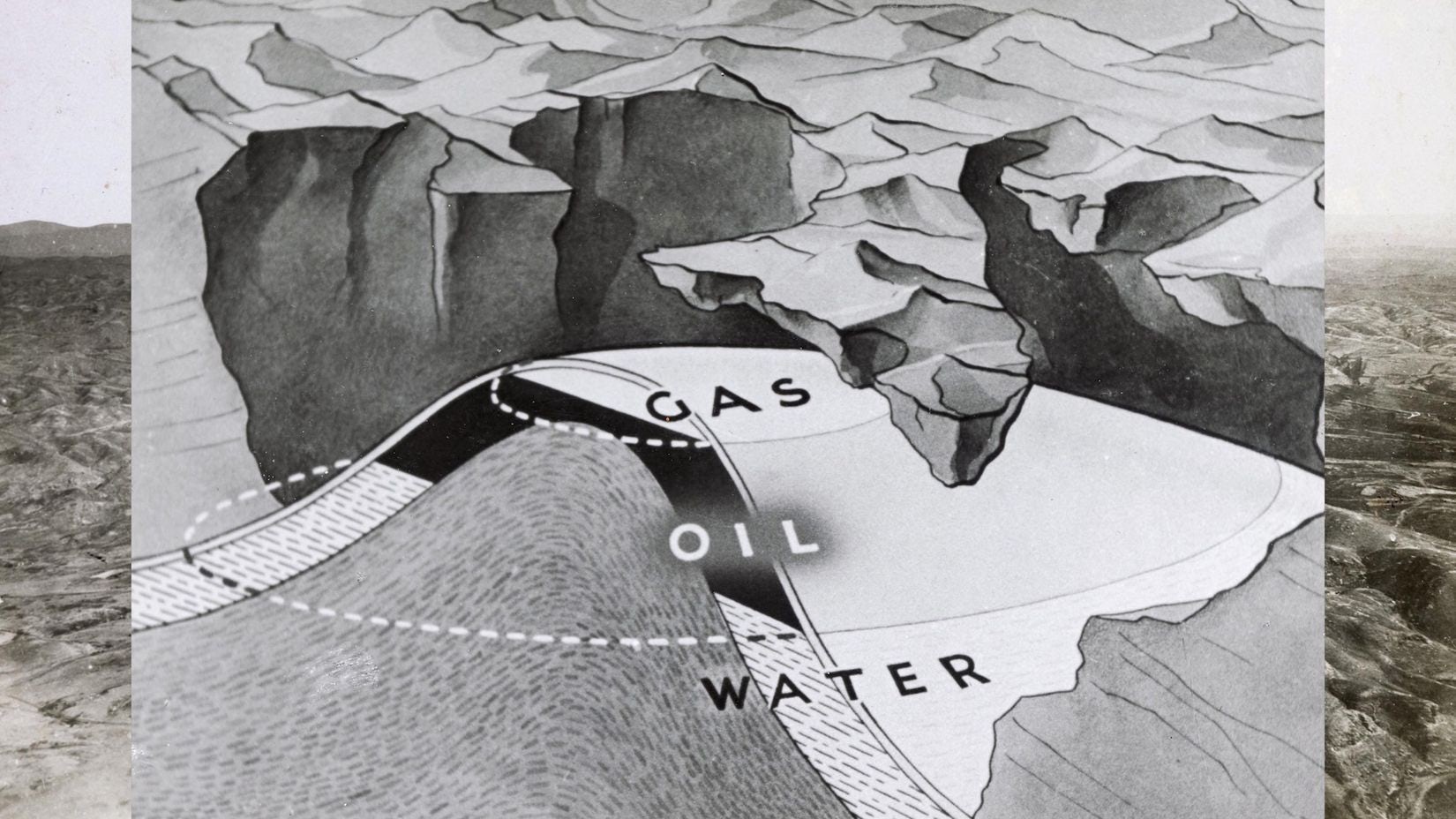

Bak’s videos radiate a profound humanity. She is attentive to all geographies and all generations, including elderly folks dancing at a ball to the sound of popular songs. Endearing at first glance, with its round framing, Bleus de travail (2020) examines the overexploitation of chicks whose feathers are dyed in pastel hues so they can be sold to tourists. In the video, they seem to be launched from springs, like multicoloured rockets, onto electrical wires where they remain perched. Gradually, we discern the sound of a machine gun. Sound always plays an essential role in these compositions. Assembly-line work in factories, labour in fields, underground toil, the agony of craft work–all constitute a through line for this exhibition. Mineur mineur (2022) directly confronts the issue of child labour. This video was produced entirely remotely during the COVID lockdowns: families in Madagascar, India, Bolivia, Indonesia and Thailand each received a kit from the artist enabling them to capture images. Children working in tin, gold, silver, sapphire and coal mines choreographed a scene resembling a school carnival dance that they are deprived from attending. Their silhouettes were then composited into cross-sectional views of narrow mining hoses, like ant colonies observed by an entomologist. With her subjects, Bak constructs collective actions that shape alternative narrations of their realities. No doubt she is among those who consider working together to be part of a vision of happiness. The result is spontaneous images, edited together in swift gestures.

These circulations on a planetary scale also appear in the work Abus de souffle (2024). The waves in question here are those along the coasts of Morocco. Puffs of air blown from traditional bellows, handcrafted by the last remaining artisan in Tétouan and held by men on the rooftops of houses, wind up on a second screen, to be aspirated by vacuum-cleaner brush attachments brandished by people along some other seashore. The artist grants increasing importance to the arrangement of her images in space. The resulting sound effect resembles a human exhalation, painful and hiccupping, from a body whose energy has been vampirized. Bertille Bak’s narratives are constructed with “images that image”–sometimes comically or ironically, but never cynically.